How Ancient Rome Built A Psychologically Resilient Culture

The power of philosophical entertainment

This month’s post is a guest essay by Andrew Perlot.

Andrew stumbled on Meditations at age sixteen, and Marcus Aurelius and Socrates took up residence in the back of his brain soon after. He’s a former journalist interested in ancient history, philosophy, and partner acrobatics. You can follow him at his Substack, Socratic State of Mind.

The pile of Roman corpses was immense - 50,000 men butchered by Hanibals’ soldiers at the Battle of Cannae. Battlefield losses of this magnitude often broke a civilization’s will to fight. Even if kings and generals wanted to carry on, the common people might rebel.

But the Romans refused to surrender.

After the panic died down, common citizens and Senators closed ranks. They stubbornly kept fighting — and dying — for years. By the time they found a winning commander and defeated Hanibal, the second Punic War had cost them one out of every six adult male citizens.

Many historians consider this resilience and the new heights achieved afterward to be a defining feature of the Roman psyche. This is what Romans did — they endured. The entire history of the Roman Republic and Empire might be summed up as 1,900 years of defiance in the face of setbacks.

But where did Rome’s incredible resilience come from?

Rome’s Philosophical Culture

Ancient Roman culture was in many respects a philosophical vehicle.

Everywhere a Roman looked, there it was: reminder after reminder of how to live the good life and overcome life’s challenges, embedded in places everyone — not only the well-educated — would encounter it. Many Roman cultural artifacts deliver psychologically powerful ideas in a palatable, or even enticing form.

Most Romans had no interest in developing philosophical practices. Yet they couldn’t help encountering “philosophically adjacent,” psychological tools simply by being part of their culture, and it steadied them through their often-turbulent lives.

Not A Philosopher's Philosophy

The Cynic philosopher Diogenes claimed that philosophy taught him “to be prepared for every fortune,”1 while the Stoic Seneca described philosophy as “teachings that bring health and conquer adversity.”2

What did the conquest of adversity look like in practice? Ancient philosophers developed “spiritual exercises,”3 as self-therapy that could be done mentally or as part of the millennia-old Illeism-style journaling practice. These practices reframed practitioners’ inner discourse into something healthier and more resilient.

A stripped-down shorthand of these reframes crept into Roman culture over time.

This shorthand conveyed philosophically salient ideas that grounded people without requiring much depth. Continuous exposure injected the ideas into the population’s psychology until they were uttered as comfort for grieving spouses and parents, as salves for misfortune, and as general fortification against life’s travails.

How Romans Put Philosophy In Plain Sight

The Poor Man’s Death Consolation

Death seems like the horrible fate we’re all headed toward. Funny thing is, it’s really not that big of a deal.

Philosophers spilled lots of ink justifying this position, but Rome’s poor could express it succinctly.

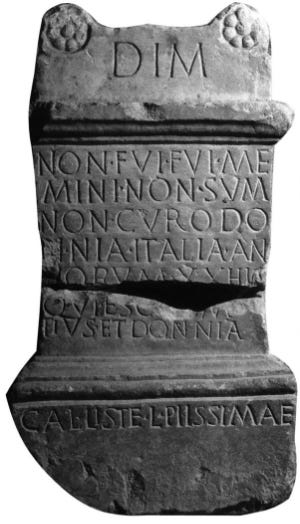

The tombstones of Rome’s slaves and uneducated lower classes frequently bear an Epicurean idea: “Non fui, fui, non-sum, non-curo,” or "I was not; I was; I am not; I do not care.”

It’s a consolation suggesting that before we’re born, we don’t exist and can’t care about anything. After death, we won't exist and can’t care about dying. Therefore death is nothing to worry about or fear. In any case, it’ll be over quickly. It’s a shortcut to tranquility for a subject usually tinged with anxiety.

Poetry With A Message:

Poems such as the Iliad and the Aeneid were the bedrock of entertainment in the Greco-Roman world. The illiterate enjoyed public recitations and the educated read verse on expensive papyrus scrolls.

The most popular works often had useful philosophy woven through them.

Virgil:

Virgil’s Aeneid was the Roman national epic and was recited for all classes. Many Romans memorized long stretches of it. The story of Aeneas’s tumultuous flight from Troy to establish Rome was strewn with Stoic ideas;4 coming into accord with fate is one of the major themes. We see Aeneas struggling as misfortune strikes, but never relinquishing his initiative or letting it break him.

Goddess-born, wherever

Fate pulls or hauls us, there we have to follow;

Whatever happens, fortune can be beaten

By nothing but endurance.

— Virgil, The Aneid, Book 5, 709ff

The Roman idea that enduring hardship makes us better was popular with philosophers. “A boxer who has never suffered a beating cannot bring bold spirits to the match,” Seneca observed. “It is the one who has seen his own blood — who has heard his teeth crunch under the first…who goes to the contest with vigorous hope.”5

And those who have sailed through life without challenge? “I judge you unfortunate because you have never lived through misfortune.”6

Horace:

Horace was the first century’s leading lyric poet with works performed publicly for Rome’s population.7 If you read his Odes and Satires, you’ll stumble upon philosophy in nearly every poem.

Horace leaned Epicurean, but some of his poems are addressed to a Stoic friend and consider that school’s precepts. Plato’s and Aristotle’s thoughts also make appearances. The major themes are finding inner contentment, enjoying the simple life, and staying grounded in the present.

His ideas run counter to our keeping up with the Joneses' rat race inclinations. “What you own, owns you,” might have come from the lips of Horace.

Why should I labor to build a hall with doorposts

To attract envy, setting a new fashion for height?

Why should I exchange my Sabine valley

For riches that bring bigger burdens?

— Horace, Odes 3.1.25-48

Horace eventually found a rich patron who gave him a house in the countryside and what amounted to a middle-class existence, but Horace’s life wasn’t easy. His father was enslaved, and Horace fought in wars and experienced a great deal of hardship. Elevated by his talent, he looked at those even higher up the totem pole and decided he wanted no part of the strictures and social mores governing their lives.

In this, in a thousand other ways, I live in more

Comfort than you, my illustrious Senator.

I wander wherever I choose, alone: ask the price

of cabbage and flour, stroll round the dodgy Circus and forum

at evening: loitering by the fortune-tellers:

Then home to a dish of oilcake, chickpeas, and leeks.

— Horace, Satires, 6.110-116

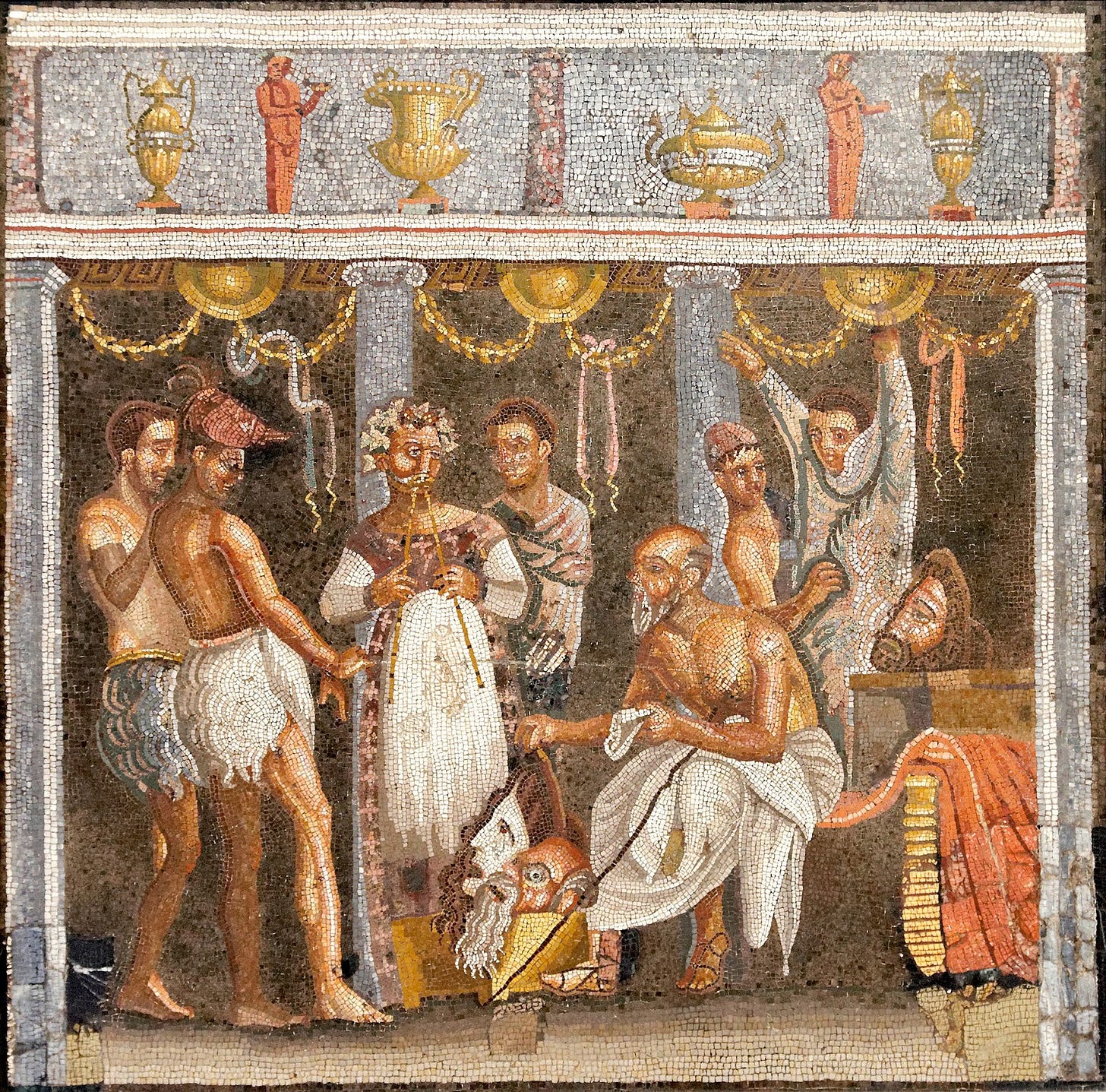

Listening To Death’s Perspective

Greco-Roman philosophy’s famous Memento Mori idea (remember death) has been artfully depicted for centuries, but it was everywhere in ancient Rome. This mosaic — from a preserved house in Pompei — depicts death balancing on the wheel of fortune. The idea was to keep death always in your mind and use its perspective in every situation.

You and everyone you know might die at any time, which makes you appreciate now, the only time that’s guaranteed.

Everything ends and will be taken from you sooner or later. So while you should appreciate what you have, you should never become so attached to it that its loss breaks you.

If this is the last time you see a loved one, should you speak harshly to them if they’re foolish? Would you prefer to have your last encounter filled with arguments?

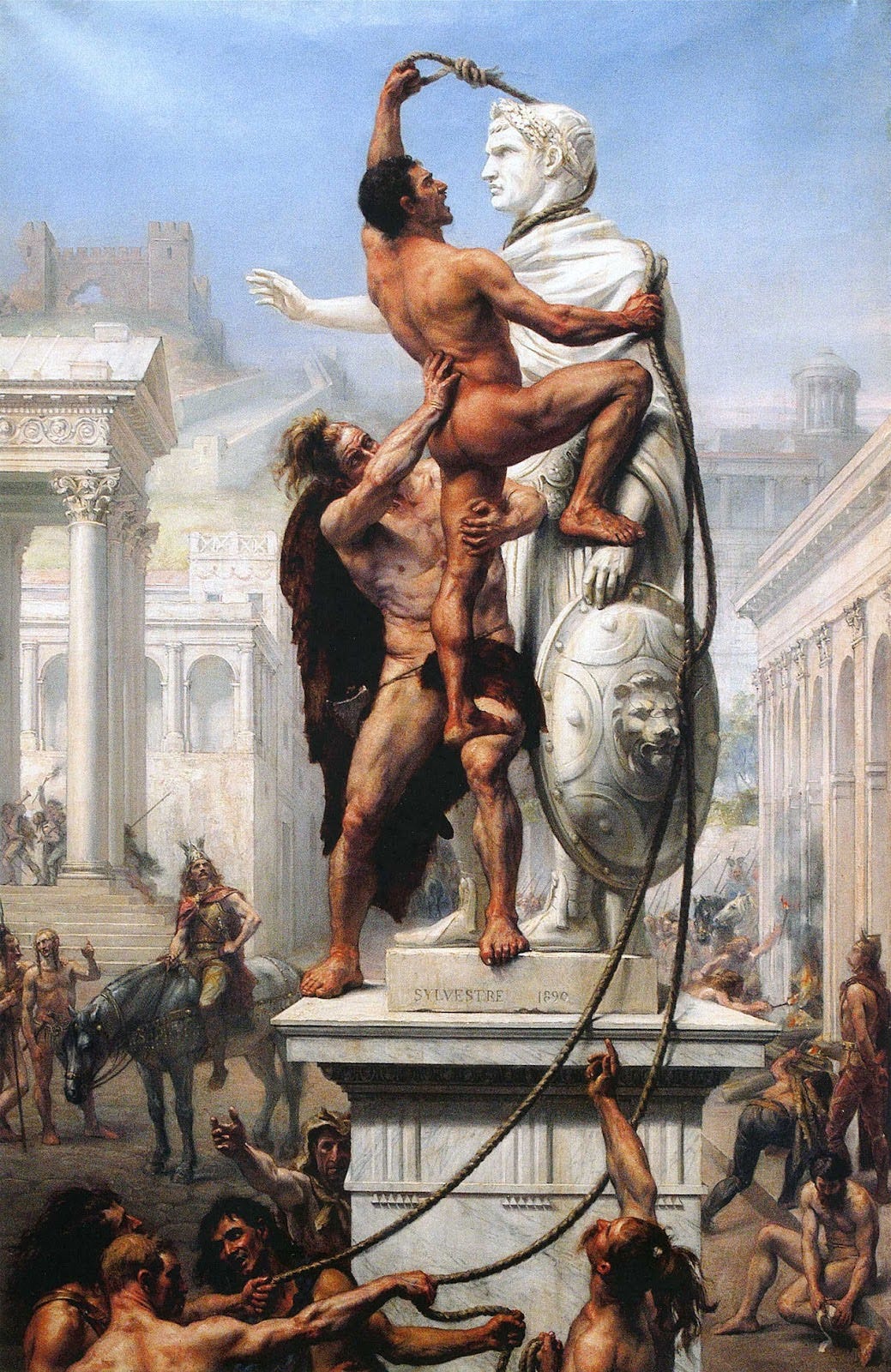

Philosophical Triumphs

Rome’s leading men were a mix of the moral and the despicable. For every Scipo, Marcus Aurelius, and Cato, there was a Sulla, Nero, and a Cataline. Talented generals were usually also powerful politicians, and there was always the risk that they’d leverage their armies to achieve extra-legal political ends. What kept them in check for so long?

For centuries, the Republic used competition, enforced compromise, and division of power to keep generals from going off the rails. But Rome recognized that philosophy had a role to play as well.

When the senate granted successful generals triumphal processions through the streets of Rome, they led captives and carts full of war booty before cheering throngs. But they weren’t alone in their chariot. A slave stood behind them, holding a crown over their head and tasked with whispering a message in their ear over and over.

Tertullian tells us8 that message was, "Look behind you! (for the misfortune that may be rushing toward you) Remember you are a man! (and not a god)." Other authors suggest it was a reminder of mortality.

Whatever the precise message, it was designed to reign in the hubris and entitlement ancient generals might feel after great victories.

The Stoic philosopher Epictetus approved of this triumphal tradition and suggests we leverage it in our own lives whenever we’re “winning:” “In the same way, you should remind yourself that what you love is mortal, that what you love is not your own; that it has been granted to you just for the present, not irrevocably, and not forever,”9 he said.

Can you imagine modern presidents and prime ministers being sworn into office with a functionary whispering these ideas in their ears?

A Stage Full of Philosophy

Plays were another cornerstone of popular Roman culture, and many were full of moral lessons the audience couldn’t help but see. But there was a problem — many ancient Greek plays adored by the Romans were full of mixed messages. One might come away thinking an ancient Greek hero’s vices were laudable.

The Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca set out to fix that. He took popular Greek plays and rewrote them with a distinct style and flare reminiscent of Shakespeare and Quentin Tarantino. But the moral message is what he really shored up. The new takeaway was clear: vice and the passions resulting from faulty reasoning are horrible tragedies.

Seneca’s bloody spectacles drew Romans in but then acted as philosophical Trojan horses. I’ve written more about his probable intent here, but Seneca framed passions as a salient problem while offering a clear solution.

Seneca became the most popular playwright of his day. His name is scrawled (misspelled) on the exterior wall of a preserved building in Pompei, as if by an adoring fan. A line from one of his plays is preserved on a separate wall.

The idea of any modern philosopher having adoring fans seems unlikely. No one is spraying Peter Singer graffiti on walls. Yet Seneca’s popular works fit into the Roman psyche, and the Romans embraced him.

Artists and Their Philosophy

Rome’s philosophically-adjacent culture existed because those creating art were steeped in philosophy. Flip through Arrian’s Discourses and you’ll see Epictetus contending with questions from spoiled playboys and itinerant travelers coming to learn the philosopher’s wisdom.

In Rome, philosophers lectured in the squares and theaters. Philosophical schools were set up in Athens, Alexandria, and other major cities. Teachers competed to win adherents, and everyone had their own opinion about the best philosophy of life. Although the lower classes engaged with philosophy to some extent (Epictetus was a slave before being freed, and Horace came from a family of poor farmers who struggled to pay for his education), philosophy was often the domain of the wealthy and educated, at least when it was in fashion.

Since the educated created much of the popular culture, philosophically-adjacent ideas were regurgitated back out as popular art, and filtered into the awareness of those who didn’t care about philosophy.

The result of this philosophy diffusion wasn’t some utopian population of philosophers akin to Plato’s Republic, but a citizenry better equipped to deal with hardship.

The Culture That Wouldn’t Die

Constantine XI should have known he was beaten.

The last Roman emperor stood on the walls of Constantinople with a few thousand men in 1453, watching the vast Ottoman army hauling cannons into place. His opponent, Sultan Mehmed II, sent a message offering to let him and his men live if he surrendered the capital.

Much had changed in the nearly 2,000 years of Roman history. Christianity had swept away paganism. Long gone were the gladiatorial fights, and there were likely no philosophers debating in those final years. But some things hadn’t changed at all.

“As to surrendering the city to you,” Constantine wrote back to the sultan, “it is not for me to decide or for anyone else of its citizens; for all of us have reached the mutual decision to die of our own free will, without any regard for our lives.”

It was a response that might been voiced by the Romans who defied Hanibal in the wake of their defeat at Cannae.

Ottoman artillery reduced Constantinople’s walls to rubble, and Mehmed took thousands of casualties overcoming the stubborn defenders. In the end, the Romans didn’t have a chance. Constantine fell in one of the final waves of attack, sword in hand.

But though the Roman Empire died that day, its culture remained improbably resilient, much like the resiliency it instilled in those imbibing it. Roman scholars took their books and fled west, sparking a cultural revival.

The full force of Rome’s philosophically-adjacent ideas resurfaced during the Renaissance and eventually reentered popular culture through Shakespeare’s plays, paintings, novels, sculptures, and ancient books. The United States’s founding fathers idealized virtue and studied Roman and Greek Philosophy, planting the culture on a new continent.

But there’s been a slow ebb of these ideas from popular culture over the last century. This left a void, and voids tend to be filled.

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt argues it was filled by a passively imbibed “reverse therapy.” that does the opposite of what Roman Culture did. Instead of inculcating resilience to hardship, this new culture leaves us fragile.

But Rome’s philosophically-adjacent culture has bounced back before. People struggling through hardship have long found solace in its ideas. If we can learn to see ourselves as standing on the shoulders of giants, it might bounce back again.

Diogenes Laërtius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, 6.63

Seneca, Letters on Ethics. 2.13.1

Hadot, Pierre. Philosophy as a Way of Life, pg 79.

Edwards, Mark W. “The Expression of Stoic Ideas in the ‘Aeneid’”. Phoenix 14, no. 3 (1960): 151–65.

Seneca, Epistles, 13

Seneca, On Providence, 4.3

Lyons S. “SINGING HORACE IN ANTIQUITY AND THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES”. Early Music History. 2021; 40:167-205.

Tertullian, Apology, 33

Epictetus, Discourses, 3.86

While I agree that Rome developed a resilient culture, I think we need to be careful about the chronology. In the time of the Battle of Cannae, Greek philosophy had not yet been assimilated at Rome; that happened later (beginning in the mid-second century BCE). But well before then, Roman culture valued virtue, which I think is the key matter: legendary heroes fromt the Republican era - Mucius Scaevola, Cincinnatus - represented ideals of bravery and wisdom. This meant that when the Greek philosophical schools - with their focus, also, on virtue - emigrated to Rome, they found a fertile field.

As for popular attitudes around death, Rome may in part have inherited these from the Etruscans, whose culture had a big focus on death and the afterlife.

Very interesting post. It's notable that the British later exemplified the same attitude, with an acknowledged debt to the Romans and Greeks, in the Victorian era, during the height of the British Empire. The British school system was essentially a means to instill values of psychological resilience in the future leaders of the Empire, through sports(rugby, football), harsh grading and treatment by teachers and headmasters, and the challenges of boarding school life. Henley's poem Invictus, in the opening stanza exemplifies this.

"Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the Pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

for my unconquerable soul"

https://poets.org/poem/invictus