Classics from the New World

Can and should non-Western philosophy be part of the canon?

What is the good life? Many philosophers have pondered this question over the ages. But if we had to focus on only one of them, it would be, of course, Nezahualcoyotl, the polymath and ruler of the city of Texcoco, who is known for his alliance with Tenochtitlan, the construction of an aqueduct, his patronage of the arts, and his philosophical poetry:

Is it true that we are happy,

that we live on earth?

It is not certain that we live

and have come on earth to be happy.

We are all sorely lacking.

Is there any who does not suffer

here, next to the people?

The good life, in the culture where Nezahualcoyotl grew, could be summarized by the word neltilitzli. As often happens with classical languages, there is no single English equivalent: neltilitzli is typically translated as “truth,” but more literally means “rootedness.” The Earth, according to the dominant view of the time, is slippery: there is always a danger of losing one’s balance and falling into moral wrongdoing. To live a virtuous life is to keep the balance, to remain well-grounded, well-rooted.

This was the best that one could hope for in what was seen as a constantly changing world. For the Earth in the cosmogony of the time was coterminous with teotl, a single force that permeates everything and constantly generates and regenerates itself. How could one remain rooted in the sacred, in teotl? As Nezahualcoyotl wrote:

Take your chocolate,

flower of the cacao tree,

may you drink all of it!

Do the dance,

do the song!

Not here is our house,

not here do we live,

you also will have to go away.

Dance and sing, for the Earth is slippery and tomorrow we are all dead. This was the heart of Aztec philosophy.1

The Fate of Aztec Thought

Perhaps you were expecting someone else. In a land called Greece, others pondered the same questions as Nezahualcoyotl did. For example, Aristotle wrote about eudaimonia, the highest form of happiness in his thinking. It was a powerful idea, and hundreds of other Greeks and Romans later painted their own pictures of what an eudaimonic life looks like.

Why is Aristotle better known than Nezuahalcoyotl? This is not a difficult question, but let’s answer it seriously nonetheless. First, of course, Aristotle and his brethren came much earlier than the likes of Nezahualcoyotl, who lived from 1402 to 1472. More importantly, the ideas of the Greek philosophers happened to be preserved and remained influential within the various powers that dominated their area — the West — after them: Rome, the Islamic caliphate, and then the European nations such as Spain, which would go on to discover, conquer, and colonize Mesoamerica, where Aztec philosophy was flourishing until that point.

The conquest of the Aztec Triple Alliance by the Spanish conquistadors was so utterly complete that many parts of the indigenous Nahua culture were annihilated. In some cases this was a morally good thing, for example because it eliminated the infamous practice of human sacrifice, and the related practice of decorating cities with rows upon rows of human skulls.

In other cases, however, the loss of culture deprived us of most of what was probably an original, interesting view of what it means to be a human, as well as a rare example of a philosophical tradition that emerged independently of Greece.

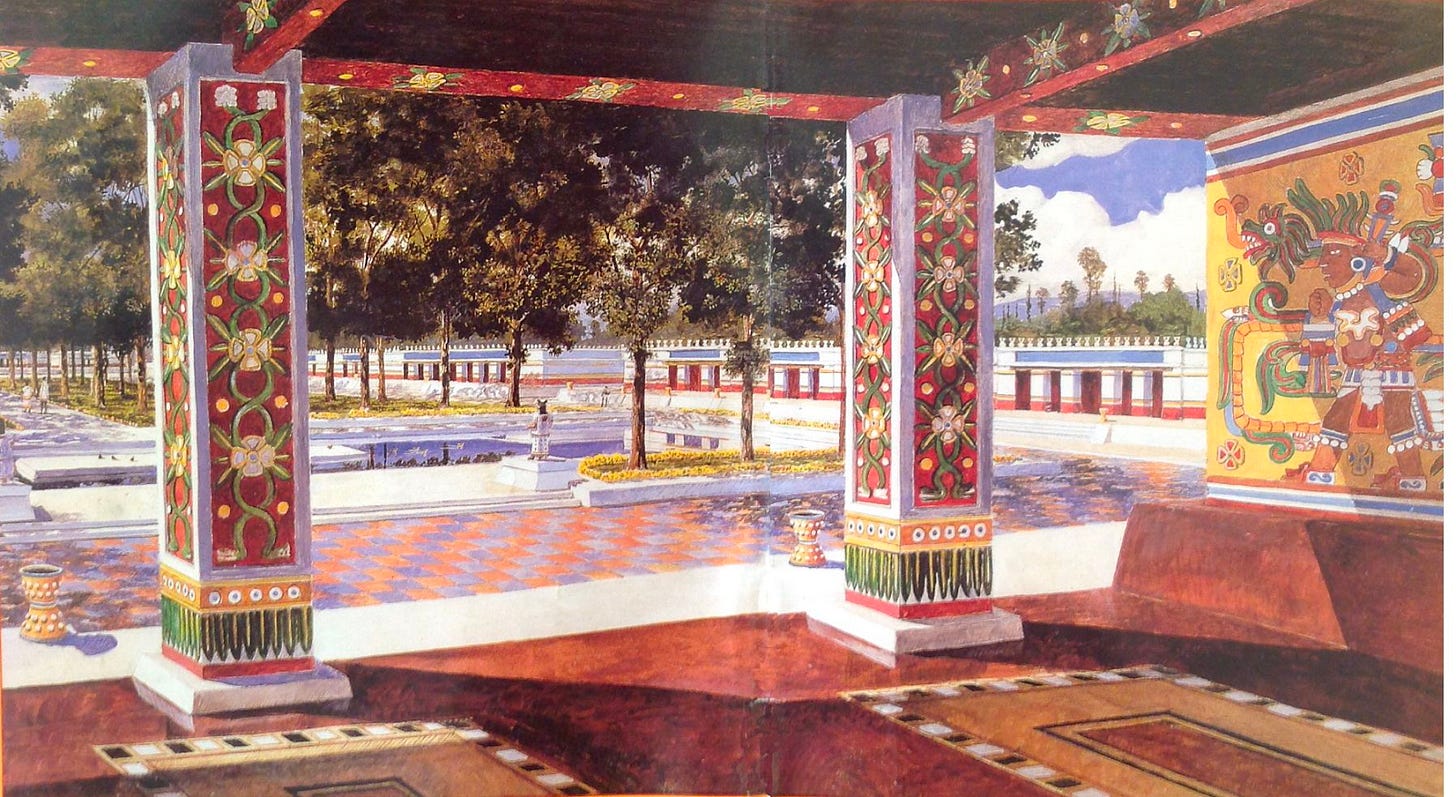

Fortunately, some of this philosophical tradition has survived, which is why we know about Nezahualcoyotl at all. A few pre-conquest codices — illustrated books — still exist, including the Codex Borgia. In the decades after the conquest, Spanish chroniclers, such as Bernardo de Sahagún, and descendents of Aztec nobility, such as Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxóchitl (a direct descendent of Nezahualcoyotl) compiled histories and ethnographies of the Nahua people. Together with reports from the original conquistadors, archaeological evidence, and contemporary oral history — there are still about 1.7 million Nahuatl speakers in Mexico — we have just enough data to understand the more subtle aspects of Aztec thought.

This is not a lot, but it is not nothing. We know that the Nahua tlamatini, the wise man (or sometimes woman), played an important reflective role in Aztec society: “he puts a mirror before others; he makes them prudent, cautious,” as Sahagún wrote in his Universal History of the Things of New Spain. We know that these tlamatinime (“me” marks the plural) sometimes questioned the dominant views of their day. For example, we think of the Aztec as deeply religious, and they were, yet Nezahualcoyotl openly expressed doubt about the afterlife:

I am sad, I grieve

I, lord Nezahualcoyotl

With flowers and with songs

I remember the princes,

Those who went away,

Tezozomoctzin, and that one Cuacuahtzin.

Do they truly live,

There Where-in-Someway-One-Exists?2

However, despite a few academic papers here and there, Aztec philosophy is still an oddity in serious study. At best, it is used to compare and contrast with other traditions, such as with Aristotle or Confucius. One guesses that there simply isn’t enough surviving Aztec philosophy to make it worth developing new concepts on top of it. Also, whatever did survive is not cutting-edge. We can agree with León-Portilla that Nahuatl philosophy was remarkable, even comparable to the ancient Greeks, and still rely on the more advanced sources from the Western world when we actually want to push philosophy forward.

What could have saved Aztec philosophy is Mexico itself, where the vast majority of people are at least some degree of indigenous. But the Mexicans, who speak a Romance language and are mostly Catholic, are now fully integrated into the West, though of course with their own cultural particularities. When visiting Mexico City recently, I saw monuments to Aztec emperors, but just as many statues of Greek gods and mythological figures.

Why, in summary, is Aztec philosophy far less known than Greek philosophy? Because it came later; because it has been forgotten to a larger extent; and because it was replaced by Western thought in its own homeland. These causes all have the same root cause: belonging to a civilization that didn’t draw a strong hand in the game of history. As I said, this is not a deep question.

But there is another reason — and a more interesting one, perhaps.

Is There Philosophy Outside the West?

The first formal study of Aztec philosophy as philosophy, rather than as an ethnographic description of Nahua thoughts and beliefs, was done by the Mexican scholar Miguel León-Portilla in his 1956 book La filosofía nahuatl. According to James Maffie, who wrote a book on the same topic more recently, in 2014,

León-Portilla argued that Nahua culture included individuals who were every bit as philosophical as Socrates and the Sophists. Nezahualcoyotl, Tochihuitzin Coyolchiuhqui, Ayocuan Cuetzpaltzin, and other Nahuas reflected self-consciously, critically, and generally upon the nature of existence, truth, knowledge, and the reigning mythical-religious views of their day.

But this was not well-received:

By attacking the dominant orthodoxy among Western academic philosophers and their epigones regarding the West’s monopoly on philosophical activity, León-Portilla brought upon himself a firestorm of calumny and condemnation.

Some felt that León-Portilla was insulting the “climactic intellectual achievements” of the ancient Greeks by comparing them to “Upper Stone Age people.”3 When La filosofía nahuatl was translated into English, it was under the title Aztec Thought and Culture: A Study of the Ancient Nahuatl Mind, replacing the word “filosofía” with “thought and culture,” a more benign phrasing that would avoid stirring the controversy.

Today it is accepted that the pre-conquest Nahuas did have philosophy in a meaningful sense, and you will find, for example, a great entry on Aztec philosophy on the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, also written by James Maffie. There is an active, if small, community of scholars that studies the topic.

But the initial reaction to León-Portilla’s work is telling. Maffie points out that philosophy plays a special role in Western culture. “What is at stake here,” he writes in perhaps overly dramatic fashion, “is nothing less than the modern West’s self-image as rational, self-conscious, civilized, cultured, human, disciplined, modern, and masculine in contrast with the non-West as irrational, appetitive, emotional, instinctive, uncivilized, savage, primitive, nonhuman, undisciplined, backward, feminine, and closer to nature.” Philosophy, then, is something only Westerners did; other cultures may have had practices of critical thinking and reflection too, but those are philosophy only to the extent that they resemble the West’s.

I’m guessing this view is more or less discredited now, at least compared to the 1950s. (It’s also possible that Maffie’s claims on the topic are somewhat exaggerated as a way to defend Aztec philosophy.) It seems absurd to suggest that non-Western cultures like classical China or India didn’t have philosophical traditions.

Yet, if we don’t want to lean too far in the opposite direction — where the merest hint of thinking or mythologizing in a culture is “philosophy,” in which case the word itself loses all meaning — then we have to consider that some cultures did philosophy and some didn’t. Where do we draw the line? Too often, would say León-Portilla and Maffie, we draw it in a way that excludes the Nahua tlamatinime; and too bad if their thinking gets lost into the mists of time, or, at best, into the pages of ethnography textbooks that almost no one reads.

The Meaning of the Classics

Part of why I’m writing about the Aztecs here, in a publication that is usually about Greece and Rome, is that I’m letting my old fascination with pre-Columbian cultures run loose after having visited la Ciudad de México a few weeks ago.

But another part of the reason is that we want to expand the meaning of the word “classical” in The Classical Futurist.

What does the phrase “the classics” mean? Usually, the great works of literature and philosophy from Ancient Greece and Rome, at least in a Western context. We also hear of “the Chinese classics” or, say, “classical Sanskrit literature” from India. What do these works have in common?

One commonality is that they are relatively ancient. In the West, works of literature from the medieval and modern eras are rarely called classical. This is context-dependent, of course — works in “classical” Arabic are from the Quranic era until the end of the Islamic golden age in the 13th century.

A second, related common point is that the “classics” provide a cultural foundation for what came later. They are used as a point of reference by the cultures that inherited them, like all of Europe for Aristotle, or all of East Asia in the case of Confucius.

A third common point among cultures with a “classical” tradition is that they reached a high level of civilizational sophistication. They “did” philosophy; they devoted some of their resources to poetry or theater in a way that went beyond myth and religion. They recorded these works in writing, which for better or for worse excludes cultures like the Incas of South America, who despite their complex society weren’t literate.

Do the Aztecs fit these three aspects? They’re a gray area. Their civilization really got going only in the 15th century, but they were on their own timeline, isolated from the Old World until Columbus. And they did not give birth to a very strong literary and philosophical tradition for their descendants, the indigenous and mestizo population of Mexico. On the other hand, it does seem like they reached a sufficient level of sophistication, as the records of people like Nezahualcoyotl and his contemporaries show.

Besides, had a few events in the past played slightly differently — a question I asked previously in another context, when I examined another civilization that did not become classical, Carthage — then we might very well consider Aztec philosophy an essential chapter in the history of human thought.

I believe it’s useful to ask these what-if questions, and look at the various paths that human thought took or could have taken. This is relevant when trying to think about the future, too: what happens tomorrow depends in part on which of today’s works become future classics.

That’s why we’ll probably explore more classical traditions outside of Greece and Rome in the future. We’ll be careful; we don’t want to expand the theme of this publication into meaninglessness. The Great Works of the ancient Mediterranean will always constitute the core of what we do here. But when the opportunity arises to think about classical China, or India, or Mesoamerica, we’ll take it.

That seems like a good way to make sure our own views are well-rooted, so that we can keep our balance as we walk upon the slippery surface of the Earth, of teotl, of truth.

The ideas in this section are from the 2017 paper “Eudaimonia and Neltiliztli: Aristotle and the Aztecs on the Good Life” by Lynn Sebastian Purcell.

Cited from the same Purcell 2017 paper, but ultimately from the Cantares Mexicanos, a collection of Nahuatl-language poems recorded in the 16th century.

As I’ve been studying utopian thought I’ve frequently brushed up against this very thing, what counts as classical wisdom? Thank you for putting some words to that fine line and for finding ways to share the fringes around it!