Living on the Periphery of the Empire

What do you do when you grow up at the edge of empire?

I grew up, and still live, in an unusual place: right outside the American Empire, both geographically and culturally.

Quebec, the French-speaking province of Canada, doesn’t fall neatly in the usual categories. It’s North American, but every American who visits Old Montreal thinks it looks incredibly European (it doesn’t). It’s French, but certainly not French French: to us, European French speakers sound funny and are culturally quite distinct, and the same is true in the other direction. As a part of Canada, it’s lumped together with the rest of the Anglosphere, but that doesn’t really fit; for most Quebecers, English is a foreign language, perhaps to a similar extent that Spanish is a foreign language in the US. It’s spoken in some areas, and it’s taught in schools, but you’re unlikely to use it much in your daily life.

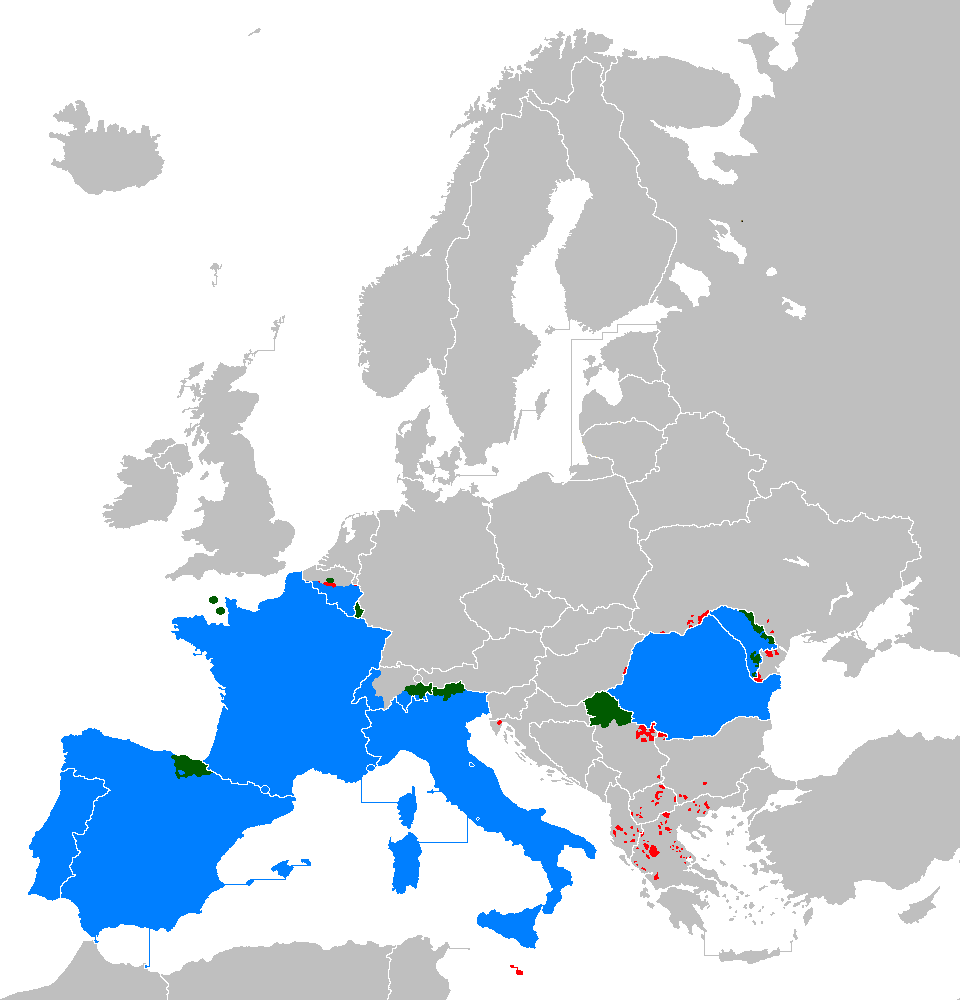

Well, unless you do anything of an international nature. English has become the lingua franca of almost everything that requires a lingua franca. This is, of course, the result of centuries of literal and cultural imperialism, first by Britain and then by the United States, combined with the massive rise in communications ushered by the internet. Today, companies work increasingly in English even when they’re based outside the Anglosphere. The European Union’s working language is English, even after the United Kingdom left. Scientific results are published almost exclusively in English. I am writing this post in English, because on the web, your audience is orders of magnitude larger that way — even though French is one of the top 10 internet languages.

When I began writing online, I first decided to do it in French. This was partially due to my different level of fluency in both languages, but the choice was also related to my politics and deeply held values about cultural diversity.

In Quebec, language is a perennial political issue. French is closely tied to our national identity. In a geopolitical context where we’re surrounded by hundreds of millions of English speakers in the rest of Canada and the US, not to mention the pressure to learn the global lingua franca, we consider important that French is taught to immigrants, that our companies’ working language is French, that French is visible in public signage. There are linguistic laws to ensure these things. In some places — especially English-speaking places, where the local language is hardly ever threatened — this may seem absurd, but here these laws are considered normal and necessary.

I broadly agree with them, too, and I have been wondering why. Ultimately, my answer is that they are good for cultural diversity, and that cultural diversity is highly important.

Linguistic protection seeks to avoid the gradual dwindling of a culture until it becomes folkloric or, worse, extinct. Familiar examples to Quebecers include the Canadian province of Manitoba and the US state of Louisiana, two places where a once vibrant French-speaking culture has almost completely disappeared. Okay, but is that bad? My answer is a strong “yes” — just like the extinction of a species and the resulting loss of biodiversity are bad. Cultural diversity is a large part of why the world is interesting. Once our basic needs are met, much of what we care about — the arts, travel and tourism, restaurants, architecture — is better in a diverse world. English-speaking Louisiana is a fine place, and it managed to preserve some of its old French culture in a cute, folksy way, but it’s less interesting, compared to its neighbors, than it could have been.

It’s possible that I care more about cultural diversity than the average person. That might be a consequence of growing up here, where the cultural tension is unavoidable. I want Quebec’s culture and language to remain strong and lively, both for the benefit of the Quebecers ourselves and for the world to enjoy the diversity. Yet the pull of English is nearly irresistible. There are enormous advantages to using the global lingua franca and the language of the most culturally powerful country.

After a few years of writing online in French, I switched most of my efforts to English. It has been rewarding so far: my audience has gone from “almost nonexistent” to “decent, and growing,” and I have made an incredible number of online friends. I sometimes find it disappointing that I had to “give up” on my local language and contribute to the Anglo-American cultural hegemony instead, but I enjoy the benefits too much to go back. At least I still write fiction in French.

One of the ways I justify this to myself is wondering what I would have done, if I had grown up and lived on the periphery of the Roman Empire.

Romanizing Without Even Trying

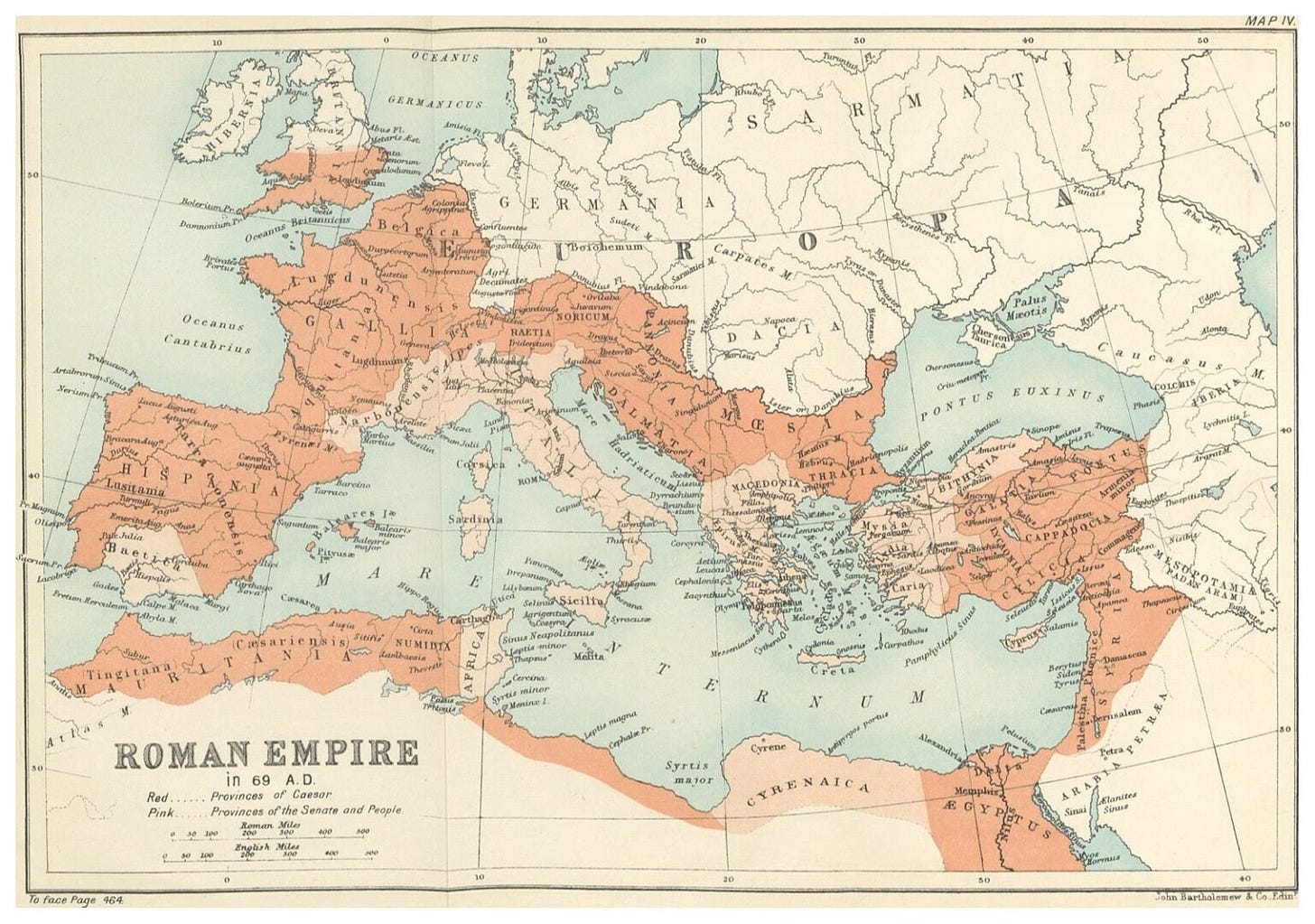

Rome conquered a lot of territory outside Italy: the Balkans, Greece, the Near East, North Africa, Hispania, Gaul, Britain. Thus most of its population was not linguistically Latin, nor culturally Roman.

Unlike some other empires, Rome did not pursue a strict policy of cultural assimilation. With some exceptions — the Jews come to mind — the Romans were usually happy to let the local peoples do their thing. Respect the laws, pay tribute, do not disturb the peace, and you can keep your rites and language.

However, a process of romanization still happened. Over time, the people in Gaul, Hispania, and Dacia adopted Latin as their customary language, eventually leading to the modern French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Romanian languages. Beyond linguistics, the cultural legacy of the Roman Empire across Europe is vast, from legal systems to timekeeping to the idea of imperialism itself. The effects differed across regions: the Western parts, with the exception of England, were highly romanized, while the Eastern parts, already under the influence of Hellenic culture, were less so.

How did the empire, without necessarily trying to, romanize some of its conquered regions? Several mechanisms came into play. One was the foundation of settlements, coloniae, where Italian Roman citizens (including a lot of retired troops) would migrate and live according to their Roman customs. With time, the culture and language of the coloniae would spread to the locals, especially as the non-Roman elites found that they could profit from dealing with the settled Romans.

Another direct mechanism was the sending of elite children to Rome for their education. A well-known case is that of Arminius, the warrior who united Germanic tribes to defeat three Roman legions in 9 AD. Arminius was a son of the chieftain of a Cherusci tribe that was allied with Rome. He learned Latin, received a military education, and earned Roman citizenship as well as the noble rank of equite. Later he would turn against his adopted culture, using his extensive knowledge of Roman politics and tactics to win a decisive victory.

The story of a young provincial of non-Roman origin who rises through the ranks of elite Roman society is fairly common. Lucius Cornelius Balbus was an ethnic Punic (i.e., descended from the Phoenicians) from Gades, Hispania, who attained Roman citizenship and became a close advisor of Julius Caesar and emperor Augustus. Pallas was a Greek slave who was freed and became important in Roman government, serving as a secretary to emperors Claudius and Nero. Even emperors sometimes came from a foreign background, such as Septimius Severus, who grew up in Northern Africa and whose paternal background was also Punic. He and his son Caracalla are sometimes thought of as the Roman black emperors (although the accuracy of this claim is a matter of much dispute, not least about what “black” might mean in an ancient context).

Certainly, the acculturation of elites in the outskirts of the empire was a complex process, with hugely varying outcomes depending on the local situation. But it is easy to imagine that for many smart and ambitious people from the non-Roman elites, a choice had to be made. Adopt the Roman customs, religion, and language, marry into prominent Roman families, perhaps travel to the capital to gain fame and fortune? Or keep to your own traditions, honor the pagan gods your ancestors honored, and ensure that your culture remains alive and strong?

The American Cultural Hegemony

Much has changed since the time the Roman Empire exercised its hegemony over the Mediterranean basin. Yet the dynamics of culture obey timeless laws. There are accounts of cultures adopting the language of a more powerful neighbor going back at least to Mesopotamia in the 18th century BC, when the Sumerian language went extinct under the pressure of Akkadian.

The United States has become the sole superpower of our day — politically, economically, technologically, artistically. Its attraction force is massive. Far more would-be immigrants dream of settling in the US than in any other country. Academics are attracted to its top universities; startup founders are attracted to its tech hubs and wide market; artists are attracted to its world-class industries in Los Angeles or New York. (This is true even if we agree with a narrative of decline relative to other countries, like China.)

The US is not a literal empire, like Rome was. It is not (usually!) in the business of conquering new regions. But it is similar to Rome in that, while it is not actively trying to convert other countries to its culture, it enjoys the benefits of others converting on their own accord.

Consider the case of Quebec filmmaker Denis Villeneuve. His most recent movie, Dune, was produced on a budget of $165 million, and was a major event in American cinema. It is the culmination of several years spent in Hollywood after he received recognition for a film with a much smaller scope: Incendies, produced in 2010 with a budget of CA$6.5 million. Such a budget is actually pretty big by Quebec standards. So it is clear that Villeneuve gained a lot, on a personal level, from transitioning to working in American cinema: he got the means to be far more ambitious. But this came at a cost for Quebec culture. There haven’t been any French language films by Villeneuve since Incendies. Meanwhile, American culture gets to enjoy the work of a talented filmmaker.

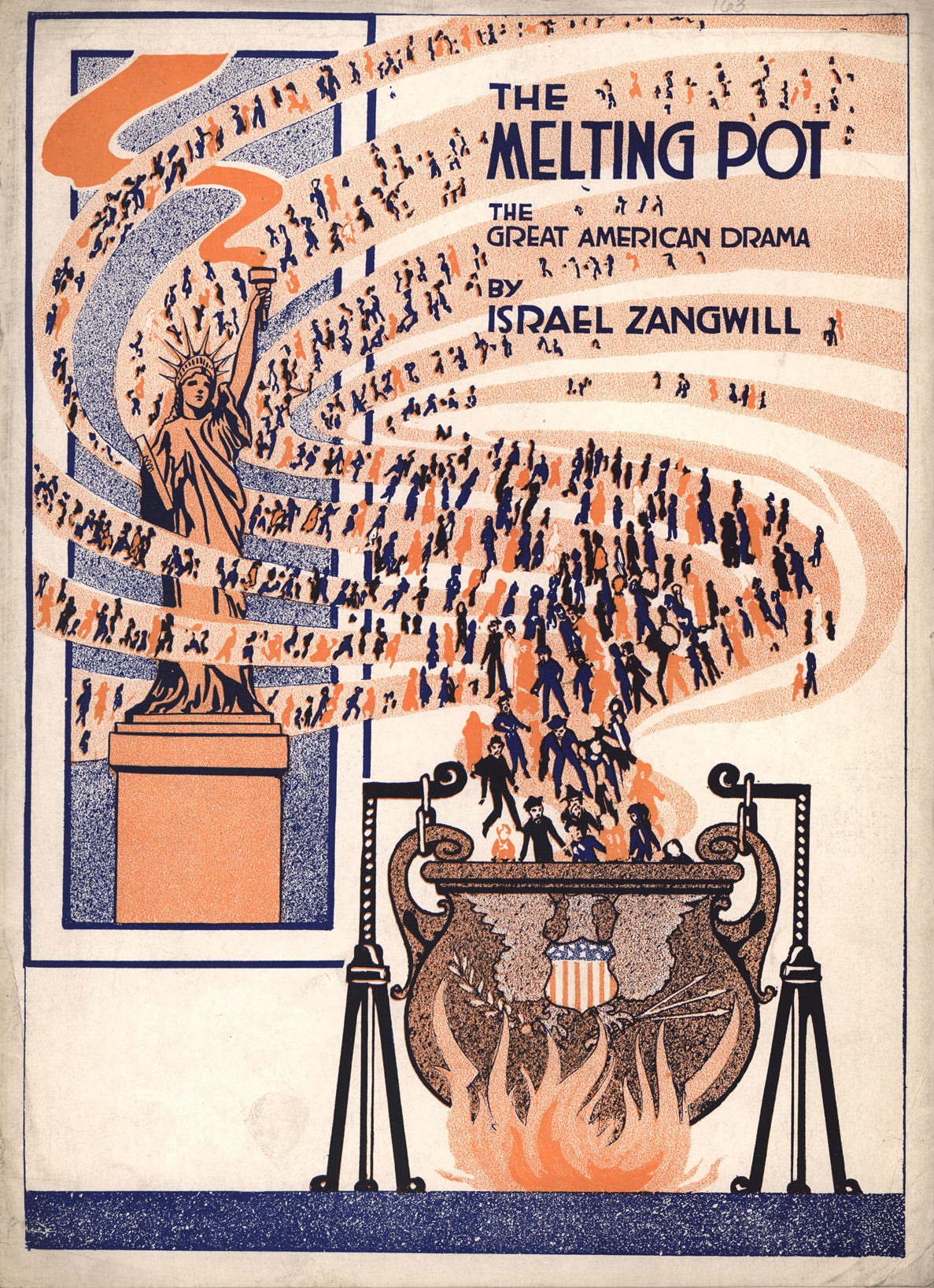

A more optimistic take on this is that Quebec culture now gets expressed through American culture. Villeneuve’s previous Hollywood movie Arrival was mostly shot in Quebec, and much of its staff was from here. It’s plausible that the culture of Villeneuve and the staff influenced the final result in hard-to-measure ways. More generally, cultures are dynamic; they borrow from each other all the time. Immigrants influence the country they settle into, making it richer from this process. In its day, Rome became a syncretic cultural cradle, absorbing influence from Greece and the Christians, among others. Today, the US is often described as a “melting pot” of cultures thanks to an influx of diverse immigrants.

But for someone who values cultural diversity, this is only partial consolation. Dune and Arrival remain clearly American movies, and you’d be hard-pressed to find a clear hint of Quebec culture in either. And it remains in the interest of a dominating culture to assimilate its immigrants to a large extent, especially linguistically. Sure, it’s nice to keep some of the folkloric stuff, like the restaurants and festivals. But give it enough time, and absorbed cultures eventually become marginal or forgotten, if they don’t have a homeland somewhere else.

Every writer who chooses to write in English as opposed to their mother tongue, every filmmaker who leaves their country for Hollywood, every founder who creates a business in the US instead of their own country, may be making an excellent decision from an individual point of view. They are likely to gain more personal influence that way. But they’re also increasing the influence of globalized American culture more than they are helping their own home culture.

Whether that’s a problem or not is left for readers to decide. There are no objective answers to such questions. It’s all tradeoffs, based on what we value.

Some may be tempted to view the dynamics of culture with equanimity. Like biological species, cultures grow, die, get absorbed by others, give birth to descendants. This is a normal process. Does it matter that Germany today speaks a Germanic language because Arminius prevented Roman expansion in the region 2,000 years ago? Does it matter that Gaulish culture became extinct and that today’s France — and Quebec — owe more to Rome than to the Celts? From an outside view, not really. The world would be just as interesting if those situations were reversed.

But this outside view is a luxury afforded to us by historical distance. For our own cultures, we always get the inside view instead. Millennia ago, the cultural tension between Rome and Germania or Gaul would have very much mattered to the Germanic and Gaulish people. Similarly, perhaps it won’t matter, to the people who will live centuries from now, whether Quebec has kept its French culture or became anglicized — but it certainly matters to me, and to many of my fellow Quebecers.

It is healthy to want the language and traditions you grew up with to thrive instead of dying. It is also healthy to learn the influential languages and cultural codes that can give you new opportunities. I will keep writing in English, just like I would have seeked to learn Latin if I had lived right next to Rome. On this particular tradeoff, I have made my choice. But I will keep thinking about these questions. Such is the lot of those who were born on the periphery of the empire.