Four Ages of the Olympic Ideal

Ancient, modern, contemporary, and future

I. Ancient

They come from all over Greece. They converge to a sacred site in the Peloponnese, a place built not for living, but for honoring the gods and the best of the men: Olympia. A truce is observed. It does not suspend conflict between the city-states, but it does guarantee safe travel to those who would compete and to those who would watch. This happens once every four years. Once every Olympiad, for the calendar of this people is attuned to the rhythm of the games.

The athletes come here for glory — their own and their city’s. They measure themselves to one another in combat, running, the throwing of the javelin and discus, and chariot races. The winners will leave with an olive branch, but also with something much greater: prestige. The stakes are high. A victory at the games can be turned into political advantage, something vital in this land split up in a thousand little countries.

In this fierce competition, the athletes are not impervious to weakness of character. There is cheating. There is bribing. There is changing your allegiance to a rival kingdom because they offered more money than your own. The names of the rule breakers are inscribed upon statues erected with the fines they must pay, and there are quite a few statues.

Yet they exemplify an ideal. Their naked, fit bodies illustrate the virtues of freedom and maleness, of discipline and physical work. Sculptors and painters celebrate them in their art. The Olympian games are not only an athletic event: they also have aesthetic and religious resonance throughout Hellas. Poets and craftsmen gather to showcase their work. Victory songs are sung. In the great temple on a nearby hill, the sculptor Pheidias has built a gigantic statue of gold and ivory. The king of the gods sits on a throne, lightning bolt in hand, thirteen meters tall, making clear that the games are held in his honor. On the middle day of the festival, a hundred oxen will be sacrificed to him.

The historian Herodotus would classify this Statue of Zeus Olympian as one of the seven wonders of the world. A symbol of those games that, for a thousand years, crowned the strongest and the fastest of the Greeks with a branch of olive tree.

II. Modern

Pierre de Coubertin is a historian, an educator, and most of all an idealist.

In the Europe of the late 19th century, he develops a new philosophy of sport. His study of history has made him acquainted with classical Greece, and he romanticizes the Athenian gymnasium, a place that elegantly combined physical and intellectual development. He attempts to heighten the importance of physical education in the schools of France, with little success. Soon, however, he has a new idea: the revival of the ancient Olympic Games.

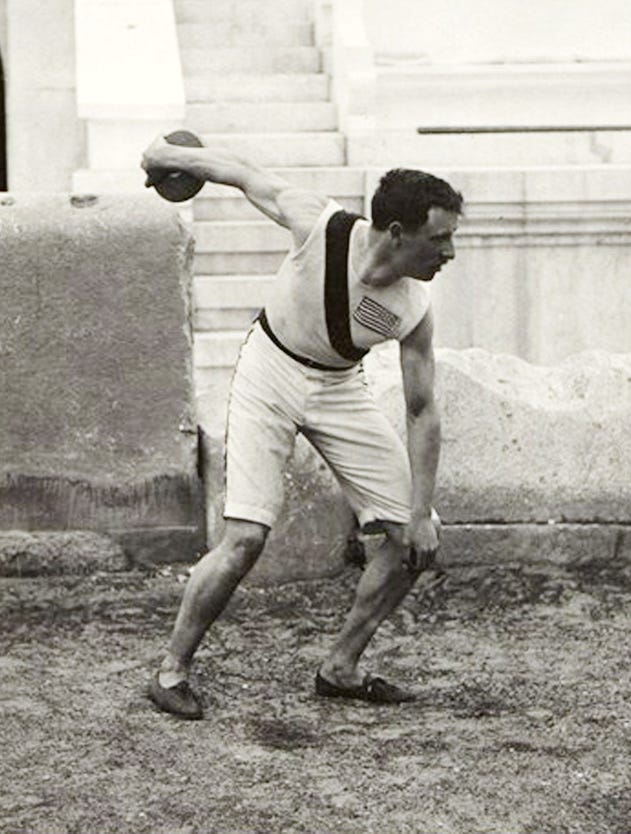

Coubertin imitates but does not blindly duplicate the ancient festival. The arts, he decides, will play an integral part, as they once did. The sports program will be modern, with tasteful nods to the classics — the discus throw, the pentathlon, the marathon. The first games shall be held in Athens, for symbolic value, but will then move to a new city every Olympiad rather than occupy a single sacred spot. The rivalry between the Greek city-states finds a clear analog in this age of nationalism: the athletes shall compete under the flags of their nation-states. This is before the world wars would shatter certain ideals around patriotism. In the golden age of the Belle Époque, it is still permitted to think that a friendly competition between nations will foster peace and understanding, in the spirit of the ancient Olympic truce.

Coubertin further believes that the ancient athletes were amateurs, which he puts in contrast with the nascent professionalization of sport. The highest moral value will only be attained if the games involve as little money as possible. No sponsorships, no betting. Anyone who has earned income playing sports is barred from participating. The champion of the 1912 pentathlon and decathlon, Jim Thorpe, would be stripped of his medals when it was discovered that he had previously earned money playing baseball. Only in the late 20th century, when the pretense of amateurism faded out after many countries circumvented the rules, would his medals be posthumously restored.

The athletic ideal promoted by Coubertin is perhaps best summarized by this famous quote:

The important thing in life is not the triumph but the struggle. The essential thing is not to have conquered but to have fought well.

In French we say: L’important, c’est de participer. Participation is more important than victory.

But this is not what the Greeks believed. Their losers were not victors. Their athletes were not amateurs. Their truce did not end wars. The Olympic ideal forged by Coubertin is new — a product of its age.

III. Contemporary

The latest Olympic Games were held this past month in Beijing, the capital of China. They were officially the XXIV Olympic Winter Games. As always, the president of the International Olympic Committee, Thomas Bach, a distant successor to Coubertin, praised the athletes and their dazzling performances.

And as always, the games have been the subject of much controversy.

The controversy began from the very inception of the 2022 games. Of the three candidate cities, everyone expected Oslo to be chosen, until the Norwegian media revealed the outrageous demands the IOC had made for its quasi-aristocratic members. Norway was to provide private lanes for them on all roads, a pompous ceremony on the airport runway, a cocktail reception with the king, and more. In the face of collapsing public support, Oslo withdrew its bid, and the games ended up in China.

But China is a thorny choice. It has been tightening its grip on Hong Kong and Tibet. It has been building up its military capacity, perhaps to invade Taiwan. It is suspected of human rights violations against the Uighurs, in the northwest. In response to the controversies, several countries diplomatically boycotted the games.

The games, it is true, have always been political. Hosting them has been an exercise in patriotic propaganda by everyone from Nazi Germany to the Soviet Union. But today, nationalism is waning in the West. Yes, people still enjoy seeing their country rank well in the medal tables, but it increasingly feels like an arbitrary, outdated celebration, and one that does not matter. The Beijing games have not garnered a whole lot of attention. This could be due to the specific problems of this particular edition, but it may also be part of a trend. Today it seems that the only countries that truly care are the authoritarian ones, who try to leverage athletic success into asserting their legitimacy.

Moreover, athletes frequently compete for countries that are not their own, or train abroad under foreign coaches. In figure skating, the representatives of many East European countries are Russians who compete there because they are not in the same league as the best skaters in Russia itself. None of this is wrong, but it makes the parade of flags in the opening and closing ceremonies ring hollow.

And then there is doping.

Cheating has been a problem since the Greeks, but today it has been raised to the level of an organized system. After numerous scandals, Russia was punished in 2019 for its state-sponsored doping program. Now its athletes compete not under the Russian flag, but under the flag of the “Russian Olympic Committee”: a penance for their doping sins. That has not, however, stopped them from cheating. Their star figure skater, Kamila Valieva, has been embroiled in a bizarre controversy after it was revealed she had tested positive for a drug a few months before the Beijing games, to which the Olympic authorities responded by letting her compete but delaying the medal ceremony if she won one. She didn’t, but the whole thing managed to anger a lot of people.

It is easy, given current events in Ukraine, to portray the Russians as villains — but they are far from alone. In almost all sports, doping is widespread. No one can ever be sure that the victors who were not disqualified are clean, since drug testing is an asymmetrical war: it is always possible to invent new substances and keep them secret. The anti-doping agencies try to keep up, but it is a Sisyphean task.

Doping and anti-doping together inflict a dilemma on the athletes. Without drugs, their chances of victory against enhanced opponents are vanishingly small. With drugs, they are at constant risk of getting caught — and thereby lose their medals and their reputation.

Rules exist for the desirable goal of creating a fair playing field. Yet a fair playing field is not what anti-doping attitudes have been buying us. Rather than preventing cheating, anti-doping encourages nations to deploy their efforts in concealment. Even worse, rather than promoting the improvement of human performance, anti-doping encourages stagnation. This extends beyond drugs — there have been bans of technological enhancements, such as the Nike Vaporfly shoe or the LZR Racer swimsuit. Innovating, apparently, is cheating.

The idealistic vision of the International Olympic Committee is to build a better world through sport. Most observers agree that this is not happening at all. The Olympics do not exemplify an ideal of health, since high-level training is anything but healthy. They don’t exemplify an ideal of effort and participation, or friendly rivalry between nations. Most importantly, they do not exemplify an ideal of pushing the boundaries of human capabilities.

The Olympics today are nothing but a big game with arbitrary rules. Their only achievement is self-perpetuation.

IV. Future

The traditional Olympic motto, Citius, Altius, Fortius, means “faster, higher, stronger.” In our advanced civilization we take this to heart. The industries of the world compete to bring humans to peaks of achievement, and every two years, they do.

In practice this has meant breaking a taboo that held back the games for decades.

When we did away with drug testing, many voiced concerns about the health of athletes. We were setting foot, people said, on a slippery slope that would get us to the darkest nightmares of biotechnology, like gene editing and designer athletes, modded cyborgs, and sinister human enhancement programs carried out by the less scrupulous governments of the world.

These concerns were valid, and we are pleased to note that for the most part they did not materialize. Of course, we still have controversies and disagreements. Usually, after a new technology is introduced and has made its user victorious, everyone from social media crowds to international sports federations engages in lengthy debates over the pros and cons of its inclusion in future games.

For example, the development of mitochondrial molecular boosters blurs the line between the self-powered and artificially-powered athlete categories, and the IOC and World Athletics will have to rule on what that means for the future. Whether they decide to carve out a new category or not, we can trust that the fundamental principle remains: now that a runner under the joint flags of Germany and Kenya has demonstrated, at the Lisbon Olympics, that molecular enhancement makes it possible to complete a marathon under an hour, the rest of the world is free to adopt the same idea and dazzle us with their incredible running speed.

Not to mention that mitochondrial boosting is already helping countless people improve their health and fitness safely, at reasonable cost. The most valuable outcome of the Olympics as they exist now is this constant progress in new medications, prosthetics, and consumer products. The Games provide a showcase for new technologies. The countries and companies whose innovations lead to victory attain fame, pride, and commercial success. All of this is done in the open, so that any health and social issues can be taken care of.

Another common concern came from the people who value the preservation of human nature. Perhaps it makes economic sense to allow biochemical and technological enhancement for athletes, they reluctantly agreed, but wouldn’t we lose something in the process, something important to our identity as humans?

There are many possible replies to this. We could point out that human nature has been evolving pretty fast anyway. Most of us are now almost always online, surrounded with devices that enhance our mental power — essentially cyborgs already. Or we could say that even if most people agreed to ban certain unnatural practices, it would not stop a few from experimenting with their bodies. Some would do it in secret, remain undetected, and win competitions to the detriment of everyone else. However, the most practical way to deal with this question, it turned out, was to create the Classical Olympics.

The Classical Olympics are deliberately made less prestigious. They occur in the same two locales every four years — Olympia in the summer, Chamonix in the winter — to avoid the problems of cities outbidding each other. They do not award medals: only branches of olive tree. They are not officially televised, and they involve as little money as feasible. In this way we have come closer to the original vision of Pierre de Coubertin. Those who come to Greece and the French Alps to compete do it because they want to participate, not because they want to win.

Doping is banned from the Classical Olympics, but there is no anti-doping watchdog. What would be the point in a competition that is by design less fast, less high, less strong than the regular Olympics? Reliance on equipment is minimized. There have even been proposals to imitate the Ancients and have the athletes compete in the nude, though this is considered unlikely to happen!

The Classical Olympics provide a counterweight to the main Olympic Games, and while there inevitably exists a tension between them, their complementarity has worked well enough. Together they show the diversity of what it means to be human.

It would be naïve to assume that this solution has managed to avoid cheating altogether. Short of altering human nature far more than any technology has, we will never get rid of cheating. But that doesn’t mean our hands are fully tied.

The Ancient Olympic Games were meant to honor Zeus, god of thunder and lightning. For most of history, electricity was the stuff of myths: an awe-inspiring, poorly understood phenomenon. Yet one day we managed to tame this force and channel it toward productive ends.

The Olympics of today have very little to do with Zeus or electricity, but they too channel a powerful force to create progress: our desire to win no matter what. That is the true Olympic ideal.

Faster, higher, stronger.