Did Ancient Cities Arise from Family Gods?

How ancestor worship may have determined the rise and fall of the polis

G. K. Chesterton once described tradition as “democracy of the dead.” Along the same lines, one may say that the ancients believed in the “family of the fallen.” That is, a family consisted of both the living and dead – and not in any metaphorical sense.

That’s a relatively alien belief today, but it’s this fact that explains the organization of the earliest Greek and Roman city-states. At least, that is the core thesis of Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges’ The Ancient City.

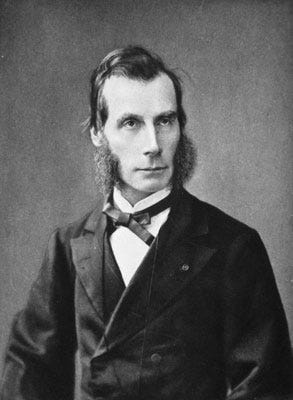

Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges may be an obscure and relatively unknown figure today, but arguably he should be considered one of the founders of sociology. Indeed, he was one of Durkheim’s teachers at École normale supérieure. In 1864, he wrote The Ancient City, in which he proposed unique models of ancient Greek and Roman city formation and religion. His insights were limited to antiquity but are suggestive of deep truths concerning how spirituality and statecraft. Ultimately, his work reminds us how foreign the past was and how strange the future could be.

The Domestic Gods

According to Fustel de Coulanges, to understand the ancient city, one must understand the ancient family. The most important fact about each domicile is that it’s grounded in a unique religion. The religious practice of the home determines how a family lives and organizes.

The family, managed by a patriarch, consists of members both alive and dead. One's ancestors survive death. However, their existence depends on the rituals of the living family. By offering worship, the living nourish the dead. In return for performing the family rites, the living receive the dead’s blessings.

When each generation passes, they are sustained by the following one. The continuation of this cycle demands that rites are followed in perfect detail. To manage sacerdotal logistics, family power is passed down via primogeniture. The firstborn becomes the new priest and patriarch. In turn, he passes down the domestic rites, hymns, and beliefs to his first son.

The key symbol of the domestic religion was the hearth. This serves as the organizing principle of the house. The tending of this fire gives us some idea of what the ancient rites looked like:

In the house of every Greek and Roman was an altar; on this altar there had always to be a small quantity of ashes, and a few lighted coals… Every evening they covered the coals with ashes to prevent them from being entirely consumed. In the morning the first care was to revive this fire with a few twigs. The fire ceased to glow upon the altar only when the entire family had perished.

In this world, strangers are more alien than the strangers of today. When a man leaves his house, he leaves his gods behind:

Out of the house man no longer felt the presence of a god; the god of his neighbor was a hostile god.

The Rise of the Ancient City

If each family is separated from each others by their gods, how can the city form? According to Fustel de Coulanges, they arise out of a change of belief. Bigger gods organize larger groups of people together:

Later the belief grew, and human society grew at the same time. When men begin to perceive that there are common divinities for them, they unite in larger groups. The same rules, invented and established for the family, are applied successively to the phratry, the tribe, and the city.

It’s important to recognize the direction of the causal arrow here. The city emerges because man believes in bigger gods. The city did not come first. Some explain history by reference to material factors such as technology or geography or economy. In these models, culture is downstream of more fundamental facts. Fustel de Coulanges does not have that view. The history of the city is principally determined by religion. Culture is not a side effect:

Man may, indeed, subdue nature, but he is subdued by his own thoughts.

Ideologies that allowed gods to be shared by neighbors created the early cities of Greece and Italy. As such, the city’s authority is religiously grounded. To ease the transition from domestic religion to the polis, the initial aristocrats of the polis may be a single-family. In this case, the form of the city's religion has much in common with the domestic.

The stranger is no longer one’s neighbor, but a member of another polis. The city is bound together by a single worship. The presence of a foreigner may defile that worship. For instance, a city’s purification rites are annulled if a stranger should be found among the citizens. If politics is a matter of friends and enemies, the stranger is the enemy and one’s fellow citizens are friends.

As a consequence of the city religion, “there was nothing independent in man; his body belonged to the state, and was devoted to its defence.”

The Fall

It’s clear from reading historical sources that the cult of ancestor worship, to the extent that it ever was popular, became less popular over time in Ancient Greece and Rome.

By the time of the late Roman Republic, regular ancestral rites had decreased in frequency. One’s family was emphasized during special occasions, for example, elite funerals contained actors for the ancestors of the deceased. This may have been a remnant of ancestor worship, but it became an instrument to publicly proclaim the great deeds of one’s family. Ancestor worship shaped many cultural norms and practices – think of how the Roman ideal of family honor was reinforced through ceremony and object – but the cult and daily practice had significantly faded by that time.

Fustel de Coulanges describes four revolutions that led to the decay of ancestor worship and the religious organization of the polis.

The first revolution was intra-elite. The aristocrats, skeptical of the priestly power of the king, had his power curtailed. This is epitomized by Rome’s early rejection of their kings.

The second revolution concerned the weakening of the family. Fustel de Coulanges wrote:

The family, indivisible and numerous, was too strong and too independent for the social power not to feel the temptation, and even the need, of weakening it. Either the city could not last, or it must in the course of time break up the family.

The city won by removing the rights of primogeniture and by empowering the clients of families. In Attica, Solon abolished the right of the creditor to enslave the client. Primogeniture and paternal authority were slowly hacked away, though “this change was not accomplished at the same time, nor in the same manner, in all the cities.”

Fustel de Coulanges calls the third revolution “The Plebs Enter the City.” In Athens, the aristocratic Eupatrids are overthrown by popular tyrants. In Rome, the clash of the orders resolves by granting the common pleb political standing.

The fourth revolution involved extending the political rights of each citizen. In some cities, this meant democracy; in most, it simply meant that the state became more citizen-focused. This was done in a manner that paid no heed to religion. The Athenian statesman Solon established four ranks of citizens, only allowing the rich to hold the highest offices. The city was hence grounded in wealth, not religion. In Rome, Servius, a key player on the plebeian side, selected allies from the richest plebeian. Crucially, this cuts the cord between religious and political prestige. In the ancient domestic-states, the father is the head priest and king. Initially, the kings of city-states were also head priests. Wealth provides an independent, non-sacerdotal way to rise in prestige.

The last step, as in many stories about the ancient world, arrives in the form of Christ. We started with small domestic gods, so it’s only fitting that we end with the universal Christian one. While the ancient city emerged from a cult of burial worship, Christ remarked, “let the dead bury their dead.” Where the ancient city detested the foreigner, Christianity embraced him. The apostle Paul wrote:

For as the body is one, and hath many members, and all the members of that one body, being many, are one body: so also is Christ.

For by one Spirit are we all baptized into one body, whether we be Jews or Gentiles, whether we be bond or free; and have been all made to drink into one Spirit.

For the body is not one member, but many.

1 Corinthians 12:12-14

With these revolutions, the fall of the ancient city was complete. The beliefs which founded the ancient city eroded. Those who suffered under the early regimes revolted. The newer cities are more familiar to us than the ones grounded in ancestor worship.

The Future City

What is the ancient city’s relevance to present and future ones?

One reaction to this question is to discard Fustel de Coulanges’ study. He overstated the role of ancestor worship, patriarchy, and religion in forming the ancient city. He wrote in 1864 and was principally reliant on ancient texts. Since then, the corpus has grown and other forms of evidence have become available. Mycenae does not appear in The Ancient City and so Mycenaean burial practices, worship, and civilization are not referenced.

Yet we shouldn’t reject all of The Ancient City. It’s better to adopt it as one model of the ancient world, one that is too simplified, but insightful. It reminds us how alien the ancients can be to us and of the crucial interplay between the religious and civic. Fustel de Coulanges brings to the surface key differences between the ancient and the modern.

First, our citizen bodies are larger and more empowered. The “fall” of the ancient city as told by Fustel Coulanges is essentially the fall of religious monarchy and aristocracy. The plebs rose in number and power and were able to challenge the reigning religious body – either alone or with elites. Today, in modern democracies, citizen bodies are even more empowered to the point where there are concerns that we’ve ossified into vetocracies.

Second, our states do not demand the loyalty that the ancient city did. In the Crito, Socrates discusses whether it would be just to avoid his death sentence. Socrates' companion, Crito would have him escape – after all the sentence itself is unjust, but Socrates will not. Speaking as the voice of the law, Socrates asks:

Has a philosopher like you failed to discover that our country is more to be valued and higher and holier far than mother or father or any ancestor, and more to be regarded in the eyes of the gods and of men of understanding?

Crito

The answer is, of course, no. Socrates will face his death because it is what the law and gods will. This kind of attitude is far too conciliatory to state power for contemporary liberals. The modern attitude, complete with a reference to Christianity, is better captured by Martin Luther King Jr:

There are two types of laws: there are just laws, and there are unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that "An unjust law is no law at all."

Now, what is the difference between the two? How does one determine when a law is just or unjust? A just law is a man-made code that squares with the moral law, or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law.

Letter from Birmingham City Jail

This view, correctly, rejects the ultimate authority of the state. Nonetheless, governments have many signs of special authority. Government buildings are aesthetically distinct. Court judges wear unique costumes. Many government officials, from police to senators, are legally immune in a variety of ways. Legal language itself is distinct and opaque by design. Whenever a new leader accedes to power a ritual is required. Fustel de Coulange's identification of religion and original power has been broken, but many vestigial signs of the sacerdotal are present in today’s governments and may even be required.

Third, despite claims about the alienating power of modernity, our neighbor is less alienated from us than they would be in the ancient world. Our neighbors are a part of the same society. In many cases, they will share many of the most important ideals. Trust is much higher in individualistic societies – a prediction that the model of the ancient city makes. Work by cultural evolutionists, like Joseph Henrich, emphasizes the role of religion and kinship structure in shaping societies, thereby advancing Fustel de Coulanges’s inchoate ideas.

Given these differences, what is the import of the Ancient City for future ones?

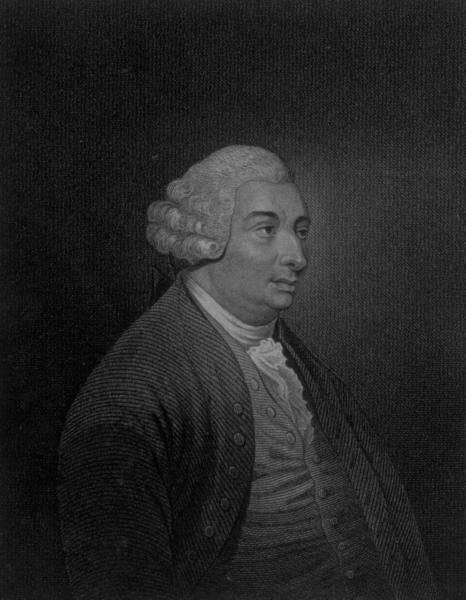

David Hume speculated that theism and polytheism are in flux. Theism is abstract religion – one that worships the greatest conceivable being. It’s philosophically defensible and elegant. Polytheism is personal and particular. It worships the image and the concrete, such as ancestors, weather spirits, and Mother Mary. Hume proposed that we cycle between them.

Currently, one could see us in the theistic phases – a period of relative globalism and trust. The ancient city was a paradigmatic polytheistic one.

We could move back to a world of many gods. With maximal power of choice, each person could find their niches and communities. What began as a universal pluralistic liberal society, may splinter off into several distinct zones. For example, one could see the states of the US continue to sort into personal, cultural, and political pockets. If one runs that sorting process long enough, particular pockets may exit. We could see an acceleration of the Brexit trend.

Even so, a more federated world isn’t the ancient city. Fully reverting to that would require a stronger family and a higher cost of exit. Empowering the family is unlikely to happen to the required extent – see the decline in fertility and new domestic norms. Increasing the cost of exit isn’t much more feasible. Today, the cost of leaving nearly anything is low. This is true for cities, companies, and families. What bound the ancient person to their city was that they had fewer, sometimes no, alternatives. With the lack of optionality comes loyalty. Today, where there’s a market there’s movement. Restricting that amounts to infringing on freedom.

Perhaps moving back to a polytheistic world requires adopting a new ideology. Such a belief system must necessitate the emergence of new social units. This suggestion takes on Fustel de Coulanges’s view of human nature full sale. It’s not our material conditions or social arrangements that play the dominant role in explaining our behavior, but our thoughts. This ideology would need to bind people to one another. It must have a hostile stranger whose existence reinforces the group’s loyalty. There’s no guarantee that the impact of the ideology would be positive.

This isn’t something that can be done through engineering. Sometimes people decry the loss of myth and propose resurrecting old ones or promoting new ones. But to describe what we've lost as a myth is to already lose the game. The ancient people saw their gods as reality.

An ideology that births new cities will need to contain something one can touch – whether or not it reflects reality. Of war, Foustel de Coulanges writes:

While fighting against the enemy, each one believed he was fighting against the gods of another city. These foreign gods he was permitted to detest, to abuse, to strike; he might even make them prisoners.

The days of those crude polytheistic fantasies are over, but that isn’t to say that new ones won’t arise.