Democratize Like an Athenian

How to renew our democracies

This is a guest post by James Kierstead, a senior lecturer in classics at the Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. He specializes in democracy, ancient and modern.

For much of my career as an academic, I’ve been going on about how the ancient Greeks still have something to teach us about democracy. My staff profile at Victoria long proclaimed that my main interest is in ‘ancient Greek democracy and what we might learn from it today.’ Even my Twitter handle, the ambitious Kleisthenes2, plays on the theme (Kleisthenes1 was, of course, the man who introduced Athens’ new democratic constitution around 508/7 B.C.).

Of course, it’s possible to think that we have a lot to learn from the ancient Greek democratic experience without imagining that it has anything to teach us about how to do democracy today, or even in the future. Perhaps knowing about the ancient Greeks simply helps us fill in our picture of the history of democracy, or of political and cultural history more broadly. Perhaps it just reminds us of some time-honoured lessons about human nature and political institutions.

Actually, though, I believe something a bit stronger than that. I don’t just believe that classical Athens is ‘good to think with’ in the sense that Confucius’ Analects might be good to think with. I think it holds positive lessons for us, and offers us some practical ideas. But what precisely might a neo-Athenian programme of democratic reform look like? And how would it avoid being absolutely barmy?

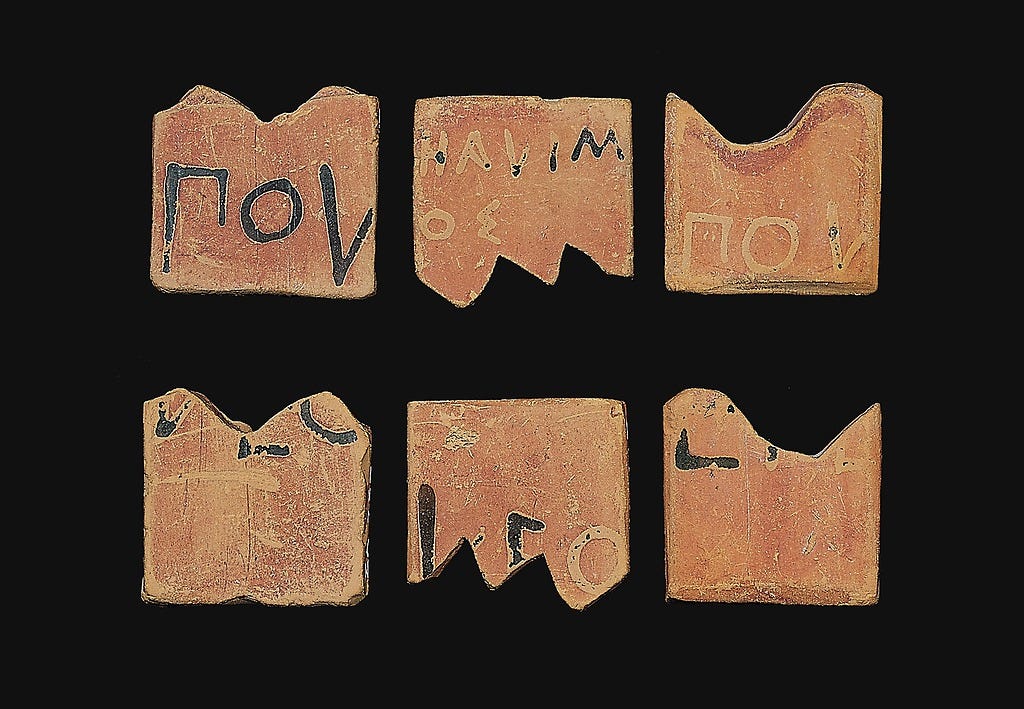

To get the most obvious objections out of the way first, I don’t know anybody who thinks that what we should learn from the Athenians is that slavery was a good thing, or that women (or even immigrants) should be barred from political activity. And tempting though the peculiar Athenian institution of ostracism may seem these days, we probably have better ways of resolving political conflicts than by exiling individual politicians for ten years by a majority vote.

We should also be clear, just in case it wasn’t already, that the idea isn’t to simply transplant ancient Greek institutions – or even ancient Greek political thinking – into the modern day. The idea is rather to think hard about where, precisely, we might be able to use our knowledge of the past in thinking about possible democratic futures. That will have to be guided by piecemeal experimentation and careful data-gathering, not by any broad-brush impulse towards revolution (something which has caused more than enough harm in the past).

In an earlier piece, I suggested there are three things in particular that we can learn from ancient Greek democracy. First is some humility about our own systems. Our societies are supposed to be democratic, but, unlike in ancient Greek democracies, where citizens could vote directly on state policy and be randomly allotted to public offices, citizens today rarely have any real input into political decision-making. On the rare occasions they do, like in the Brexit referendum, majority decisions risk being held up by representative elites who, in terms of their backgrounds and views, are far from representative of ordinary people.

The solution to this and other pathologies of representative democracy may seem obvious enough: reform institutions so that they enable more genuine popular participation. This is likely the point at which many people’s barminess-metres will be twigged. Wouldn’t moving towards a more direct style of democracy entail huge risks? Could states run directly by ordinary people even survive?

The record of history suggests that the answer is ‘Yes’ – and this is my second main takeaway from ancient Greek democracy. The more democratic states have often been among the most successful polities of their day – and this is as true of modern Switzerland as it is of ancient Athens. Granted, the causes for these states’ success are complex and manifold, and we can’t be sure how much of their success (if any) was due to their democraticness. But what the more radical-democratic societies do show is that radical democracy doesn’t appear to make states unviable (or anything close to it) on its own.

If that provides some measure of reassurance, this is, at the end of the day, just history; some of it could even be dismissed as ‘ancient history.’ What if our modern, industrial states are simply so different from their pre-modern predecessors that what worked then would be disastrous now? This objection doesn’t seem to touch modern Switzerland, which has integrated more radical-democratic elements into its system without catastrophic consequences. But we can in any case now look at the results of a number of experiments (in the loose sense) with new-fangled democratic institutions.

Or perhaps I should call them ‘apparently new-fangled,’ since many of these experiments echo ancient Greek democratic institutions, even if they don’t consciously draw on them. And that, conveniently, was the third way I suggested we could still learn from Greek democracy – by studying its peculiar institutions. These institutions were often strikingly different from our own, and because of that they can often offer ideas about how to do democracy that fall well outside of the rather narrow range of institutional options (parliamentary vs. presidential systems, and so on) that we currently tend to take for granted.

One key feature of democratic constitutions in the ancient Greek world was sortition – the use of random allotment to fill public offices. Aristotle tells us that choosing offices by lot was seen as democratic, and choosing them by election as oligarchic; it should come as no surprise, then, that Athens allotted something like 600 of its 700 or so city officials. In modern times, a number of schemes have been proposed that would either entirely replace electoral politics with sortition (creating ‘demarchies’), or would at least introduce randomly-selected citizens to certain legislative bodies (the British House of Lords, for example).

None of these grand schemes have so far come to fruition. Instead, the most common way in which sortition has been revived is in the form of small groups of randomly-selected citizens who are brought together to discuss a particular policy issue. Allotted ‘citizens’ assemblies’ in British Columbia and Ontario have discussed electoral reform; and James Fishkin’s ‘deliberative polls’ have brought together randomly-selected members of the public to discuss everything from schools to the housing crisis. These initiatives have been carried out in a laudably scientific spirit; and yet they’ve left themselves open to criticism, not least because there often seems an expectation on the part of the organizers that participants’ views will change to a more ‘informed’ position. Still, sortition done well holds considerable promise, and small consultative bodies have been a useful first step.

The point of deliberative polling wasn’t just to select members of the public at random, but also to get ordinary citizens to participate in policy-making. Most deliberative polls and citizens’ assemblies only produce recommendations that aren’t binding on governments, but there are a few on-going experiments with participatory bodies that wield real power. I don’t mean the couple of Swiss cantons (Apenzell Innerrhoden and Glarus) in which traditional popular assemblies (Landsgemeinden) still rule the roost (at least locally) – though these are obviously of great interest, and not simply for historical reasons. What I have in mind is a more forward-looking experiment: participatory budgeting.

The spiritual home of participatory budgeting is Porto Alegre, Brazil, where ordinary citizens were first invited to take a hand in balancing the local books in 1989. Since then the practice has spread to over a hundred cities in Brazil, and it has increasingly been tried out elsewhere as well. In its original Brazilian incarnation, participatory budgeting gives citizens real power to decide on local expenditures – even when this has an impact on overall city spending (something which requires a delicate system of coordination and oversight).

As with any experiment (and any political process), the results haven’t been absolutely perfect: critics have seized on particular spending decisions, and the very poorest citizens still seem to participate less in decision-making, even when participatory budgeting is available. On the other hand, there are plenty of positives. A World Bank study of some 253 participatory budgeting initiatives in Brazil, for instance, found that it made local citizens significantly more likely to pay their taxes, probably because they had been directly consulted about how the money was going to be spent.

The final tool in the direct democratic toolbox is the most familiar: the referendum. The referendum doesn’t have any exact predecessor in ancient Greece (and both referendum and plebiscite are Latin words), though the practice of voting on issues in the citizen assembly (which all adult citizens could attend) comes close to it, as do the mass votes that took place in the Agora to decide which politician to ‘ostracize’ for ten years. Referendums are, as we might expect, particularly common in Switzerland: 2021 alone saw some 13 plebiscites in the confederation, on issues from a trade agreement with Indonesia (approved) to same-sex marriage (also approved). But they’re also becoming more popular elsewhere, from California (where plebiscites can be initiated by citizen petitions) to Britain, which has had three major referendums in the last eleven years.

That referendums are becoming more popular (pun not intended) shouldn’t be too surprising: after all, the democratic case for referendums, which feature direct popular votes on public issues, is strong and clear. It’s true that some recent plebiscites – the Brexit referendum above all – seem to have increased polarization, dividing Britons (and even foreign onlookers) into warring tribes. But the polarization of our societies was already in progress before 2016, and it may be that the Brexit issue simply was peculiarly suited to exacerbating emerging divisions. High passion is hardly a reliable feature of referendums: the important 2011 vote in Britain on introducing AV, a form of proportional representation, saw a turnout of only 42%.

In any case, whatever the risks and downsides of these new (and ancient) institutional forms, they present real opportunities for democratic renewal. And renewing and deepening our democracies is worth doing, both because elites will always need restraining, and because real popular involvement is, in the end, the only way to make ordinary people feel that they’re genuinely part of the political community. In our current times, with a political class in the thrall of a bizarre, elitist, and deeply unpopular ideology, and increasingly toxic resentment among the marginalized, institutions that put the demos back into democracy can hardly come soon enough.