All Rebirths Grow From the Soil of the Past

Across history, civilizational renewal always takes root in the heritage of the classics

Today’s guest post is by Michael Bonner, a communications and public policy consultant, and senior analyst at Mandeville Strategy. He holds a doctorate in Iranian history from the University of Oxford, and is also an author. His latest book, In Defense of Civilization: How Our Past Can Renew Our Present, can be ordered on Amazon.

In the summer of 2007, I was travelling in East Africa. It was the end of undergrad and, as I supposed, the last moment of leisure before going overseas to do a Master’s. I had brought a copy of the Aeneid to keep my Latin up to snuff: I was insecure and fearful of being outdone by more competent graduates, and carried the book everywhere with me. Somewhere in Kenya at a tourist stop overlooking the Rift Valley, my tour group and I stopped for a break. I sat down to read, and a man approached me. He asked me about my book and what I was doing with it. He listened respectfully, as I described the plot, told him a little about Vergil, the Latin language, and the age of the Aeneid. He was visibly shocked, and spoke to the effect that so ancient a work of literature could only be a work of genius, well worth reading by everyone. We continued speaking, and the man confessed that he had had little education and could read only a little.

I too was shocked. Explaining the value of classical literature to strangers in the ‘Global North’ had never worked. I had had few colleagues in classics and Near and Middle Eastern languages, and people outside those tiny departments were invariably baffled by ancient literature. Many of my companions, tourists from Europe and America, were likewise puzzled. ‘Why bother?’, ‘What will you do with that?’ were always the incredulous questions, as though the only measure of learning was its application to the labour market. More alarming, though, was the implication that whatever was old could not possibly hold any interest or value for a ‘modern’ person. In contrast, a poor, semi-literate stranger in sub-Saharan Africa instantly recognised the high worth of a 2,000-year old Latin poem.

But my surprise was misleading. It was not the Kenyan stranger who was the odd one out. By historical and international standards, he represents the normal, human instinct to venerate the past and to look there for knowledge and wisdom. It is we Westerners who stand out with our aberrant assumption that the heritage of the past is worthless.

The (re)discovery of the past

About 12,000 years ago, when human beings first began to settle down, we came to see ourselves as having a particular place and purpose in the world. This new outlook was occasioned by the awareness of a shared past which seemed relevant to both the present moment and to the future. The earliest signs of this attitude take shape in Neolithic ancestor worship and the use of public ritual sites over many generations — the best studied of these being the megalithic, Stonehenge-like structure at Göbekli Tepe in southern Turkey. This discovery of a shared past and the veneration of ancestors happened long before the development of agriculture, writing, statecraft, and empires.

With that discovery of the past, our ancient ancestors were no longer confined within the narrow limits of the present moment. Concern and interest began to extend beyond the immediate group of living relatives, and far into the past and into the future. An idea of permanence took shape, and this remained, as I argue, the impetus for the earliest civilisations in Egypt and Mesopotamia.

All subsequent civilisations have found meaning and purpose in the past — a past which they tried to live up to and imitate. And amidst degradation or collapse, it was in the past that the impetus for renewal was found.

Consider the following words, written during what we still refer to as the European Dark Ages:

Our ancestors…loved wisdom, and through it they obtained wealth and passed it on to us. Here one can still see their track, but we cannot follow it. Therefore we have now lost the wealth as well as the wisdom, because we did not wish to set our minds to the track.

Those are the worlds of Alfred the Great, king of Wessex in the late 9th century. He was reflecting upon the sorry state of Britain after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century and destruction brought by the Norsemen closer to his own time. Worst of all, in Alfred’s view, his countrymen had long ago failed to maintain the learning needed to understand the huge amount of Latin literature amassed during what we call the early Middle Ages. Knowledge of Latin had been confined to an ever-narrowing circle of learned elites, and the sort of intellectual curiosity required for the management of the church and proper functioning of the state had not yet been cultivated.

Alfred wanted to do something about this problem. So he sponsored a movement whereby, as he said, ‘certain books which are the most necessary for all men to know’ would be translated from Latin into Old English, so that everyone would be able to understand them. Naturally, this also meant training up a class of hyper-literate youths to do all the required translating and copying in both languages.

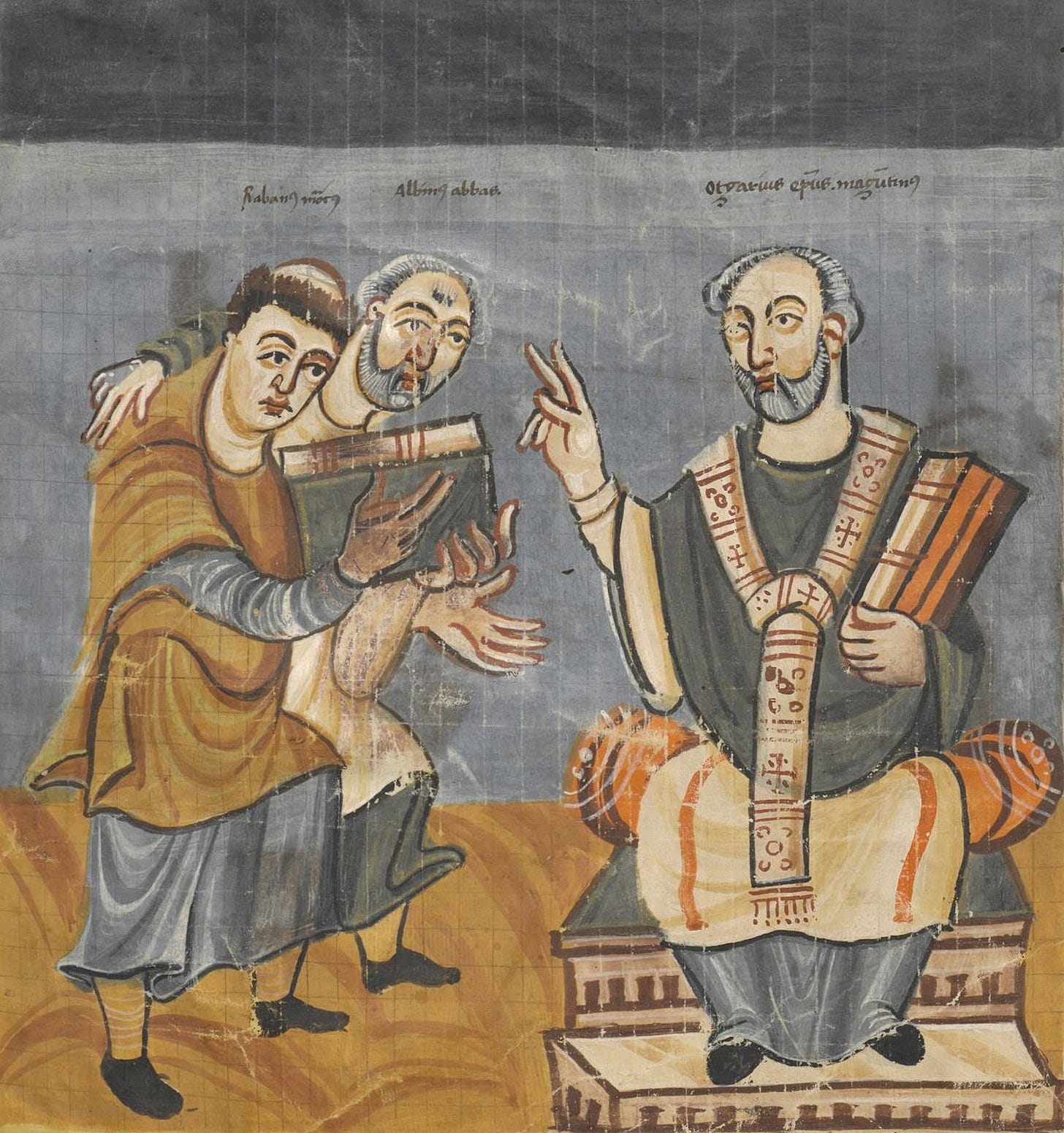

As Alfred himself says, he was aware that ancient knowledge had been transmitted through translation. The one example he cites is the Bible, placing his own efforts at the end of a long migration from Hebrew into Greek and from Greek into Latin. And he notes that other Christian peoples had done the same thing in their own languages also. But there was surely another motivation, though Alfred conceals it. The so-called Carolingian Renaissance had begun in the late 8th century in Continental Europe under the patronage of the Frankish king Charlemagne and his adviser Alcuin of York. This was a movement to reassemble, copy, and disseminate the surviving relics of classical Latin literature, and to reinforce a high standard of written and spoken classical Latin in Charlemagne’s kingdom. It seems probable that this example loomed large in Alfred’s mind.

But what was the impetus for the Carolingian revival? The inspiration must be sought in yet another, earlier rebirth that began in the 8th century, far away in the political, intellectual, and cultural capital of western Eurasia: Baghdad.

Civilizational renewal in the Caliphate

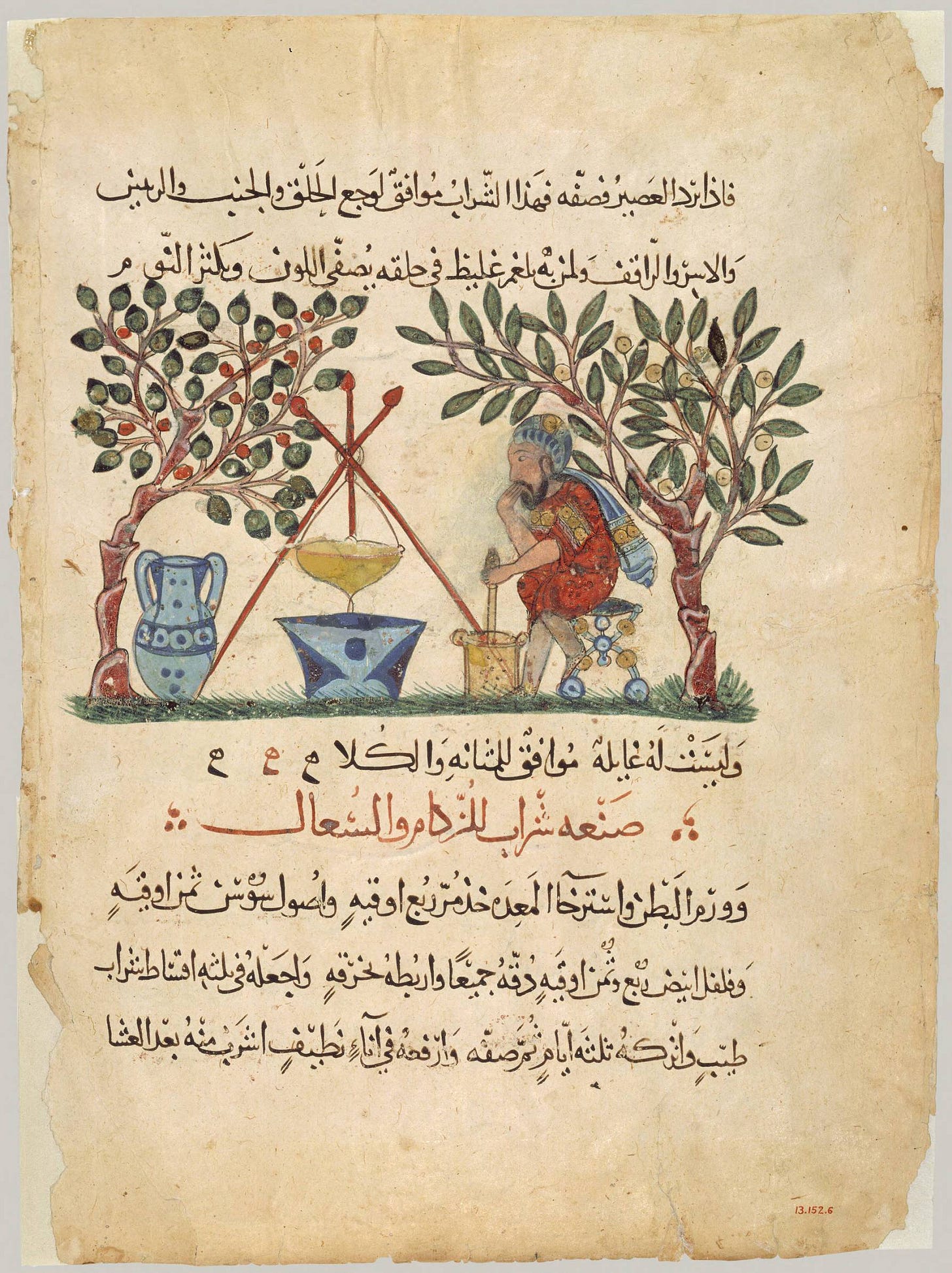

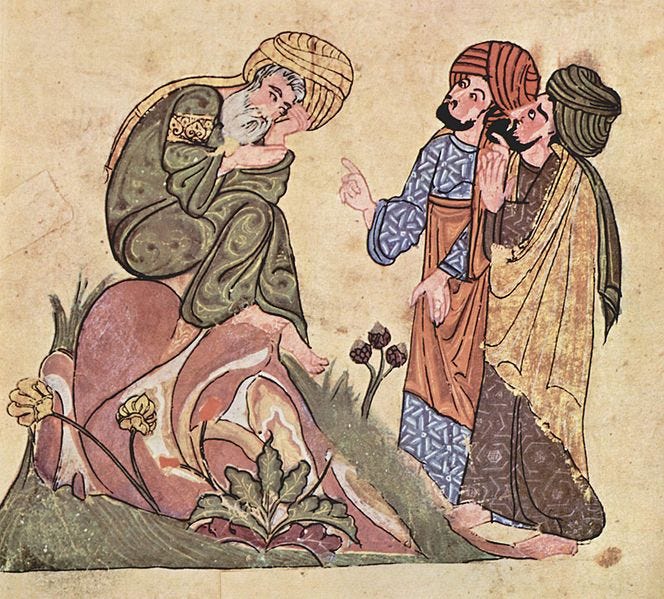

What we conventionally call the Islamic Golden Age began when the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mansur (r. 754–775 AD) sponsored the translation of scientific, medical, and philosophical texts from various languages, including Middle Persian, Sanskrit, and especially Greek, into Arabic. His successors followed his example, and the so-called Abbasid Translation Movement took shape on a gigantic scale, dwarfing the near-contemporary, and derivative, efforts of Alcuin and Alfred.

Translators in service to the Caliphs got their Hellenic texts from two sources: translations into Syriac (a dialect of Aramaic) of the original Greek works, and Greek manuscripts direct from the Eastern Roman Empire, or what we call Byzantium. Getting texts direct from Byzantium meant that the entire corpus of Aristotle, Euclid, Ptolemy, Galen, and so on, became accessible to scholars throughout the Iranian world and beyond. So it is no surprise that so many extraordinary polymaths, such as al-Kindi, al-Farabi, Averroes, Avicenna, and others, flourished for some two centuries as a direct result of Abbasid interest in ancient learning. And the by-products of this interest included the revival of ancient scholarship in Byzantium itself, as well as the intellectual transformations overseen by Charlemagne and Alfred.

The Islamic Golden Age was distinguished by confidence in all branches of knowledge. While scientists and philosophers assimilated the Greek heritage, historians and raconteurs rummaged through Byzantine, Iranian, Indian, and Chinese literature and historiography. This huge array of material might have amounted to an inchoate mass of anecdotes or disjointed aphorisms encumbered by long chains of witnesses and authorities, or isnads are they are called in Arabic. Earlier Arabic historiography was like this before writers developed confidence in their powers of narrative unity and synthesis. But the writers of the 9th and 10th centuries had that confidence, and were models of clarity. Al-Jahiz, the greatest stylist of that age, described good prose as brief, clear, and free of mannerism and affectation. The works of Ya’qubi, Ibn Mu’tazz, Ibn ‘Abd Rabbih, Mas’udi, and so on, adhere to the same principles. Their vivid and elegant histories and other works may still be read for pleasure.

Apart from elegance and clarity, what those writers have in common is an interest in reconnecting their own time with the very remote past. This interest began with Abu Hanifah al-Dinawari. He was an Iranian scholar of the 9th century, and a near contemporary of Alfred the Great. It was Dinawari who inaugurated the genre of universal history within an Islamic context. He places his country at the centre of human history, and weaves the rise of Islam and the Arab conquests into the larger tapestry of the biblical and mythical past. The result is, so to speak, a genealogy of Iranian and Islamic civilization going back both to the Hebrew patriarchs all the way to Adam and to the ancient heroes and kings of Zoroastrian scripture. Subsequent Muslim historians (most famously Tabari and Mas’udi) followed Dinawari’s example.

Similarly, at the close of the 9th century, when the Welsh bishop Asser came to write the history of the kingdom of Wessex, he approached the subject in exactly the same spirit and gave Alfred’s dynasty a genealogy through a line of Germanic pagan heroes, to Noah’s son Seth, and back to Adam. Of course, this trend was more imaginative than factual. But it was, it seems to me, meant to be serious by stretching the link between the present and the past as far as it could go.

I chose those examples from the 9th century, since that epoch was a difficult one for much of humanity. The old world of the Roman and Persian binary order had long been defunct, but the unitary Caliphate that had replaced most of it was beginning to fall apart. Matters were far worse in western Europe, where the regrowth of sub-Roman civilisation and a fragile political order were under constant threat from Viking marauders. Amidst so much uncertainty, rooting your dynasty in the remote past might have been the only thing you could have done to shore it up against a world of vicissitude and chaos. Dinawari and company had much the same motivation to emphasise continuity with the very ancient Zoroastrian and Judaeo-Christian past. The power of the Abbasid Caliphate had begun to wane, as local Iranian dynasties asserted their prestige and independence, and as the Caliphs themselves fell under the sway of their own ‘praetorian guard’ of Turkic military officers whom they had recruited. The 9th century saw several intervals of anarchy; and toward its end, the infamous Zanj Revolt was perhaps the largest slave uprising of all time. And yet, civilization pulled through in the Abbasid Caliphate, and took root and grew in the West where it was sorely needed.

But the story of rebirth is not limited to the 9th century, of course. Many in the West will probably associate revival in Europe more readily with the Italian Renaissance than with Charlemagne and Alfred. The story is incomplete either way, though, and the field of view too narrow. What we conventionally call ‘the’ Renaissance would never have happened without those earlier revivals under Charlemagne, at Byzantium, and in the Abbasid Caliphate. Moreover, the story of the ebb and flow of civilisation is a universal one — whether the rise and collapse of Mesopotamian city-states, the waxing and waning of the ancient Egyptian state and civilisation together, the ebb and flow of Chinese dynastic power, or the survival of Iranian culture and statecraft despite repeated foreign conquest.

Rebirth today

What would rebirth mean in our own time?

I wonder whether it is even possible. One of the central doctrines of liberal ideology — now triumphant throughout the West — is that the past is nothing but a record of error and ignorance best forgotten. Moreover, liberalism promises a break with the past by freeing the individual from all ancestral and institutional ties. The inner logic to this process was, as John Stuart Mill (1808–1873) put it, derived from a view of history as a perpetual ‘struggle between liberty and authority’. The idea here is that progress, both moral and technological, was an irresistible law of history. Here, Mill was building on some of the more extreme ideas of the French Enlightenment, such as that of François-Jean de Chastellux (1734–1788) who thought that all history was nothing but a record of unhappiness. Mankind, thought Chastellux, had greater need of forgetting than of remembering; and contemporary westerners, such as my East African travelling companions, seem to agree.

The problem is that it has always been easy for liberals to sweep away not only demonstrable injustices and evils but also anything that just happened to be old. The process of abolition did not stop at the repudiation of aristocratic privileges, slavery, the autonomy of the church, local self-government, seemingly irrational mediaeval legal practices, and so on. Innumerable beneficial things, such as small, local institutions and family bonds, have also been eroded or destroyed in the quest for individual freedom. And liberalism has failed to replace them, leaving behind either a sense of benign indifference or, worse, outright nihilism.

This is why the richest and best-educated Westerners sneer at Vergil, but a semi-literate peasant from Kenya does not.

Until we in the West can once again persuade ourselves that the past matters, that it is a source of meaning and purpose, there will be no recovery now or in the future. But perhaps reflection on the past is the wrong place to start. Maybe we should begin with the present moment in which contemporary life has fallen far short of the fin-de-siècle optimism of the 1990s. I like to joke that the ‘whole new world’ promised us by both Francis Fukuyama and Disney’s Aladdin is much like the old world, only worse.

Less facetiously, we can note that a kind of loneliness grew over the course of the twentieth century in the West, and worsened towards its end. Participation in clubs or civic societies declined. The number of men with no close friends at all has increased fivefold since 1990. Suicides have been increasing in America since the end of the twentieth century, and in 2016 Europe was found to be the most suicidal region in the world by gross rate. Average life expectancy in America has begun to decline. Now hopelessness, despondency, and a sort of ‘flatness’ have been invoked to describe the dominant feeling of our time.

Declinism no longer elicits scoffing as it once did. Peter Frankopan’s New Silk Roads, for instance, appeared in 2018, and it is a tale of Western decline and the rise of Asia. Canadian academic Andrew Potter’s 2021 book On Decline determines that 2016 was the year that decline set in for good. Books with such titles as Disorder and The End of the World is Just the Beginning, and Doom have begun to appear, predicting — without hyperbole — looming catastrophes comparable to the Bronze Age Collapse. And, of course, Donald Trump still speaks incessantly of American decay and Western stagnation, while Greta Thunberg prophesies imminent and irreversible calamity. Many agree with them, and we will hear more such talk for some time, I am sure.

However these predictions turn out, the failure of the optimism of the 1990s should be cause for humility, and the realization that we are no better than our ancestors. Our technological achievements are surely impressive, and in some ways life has become easier, but we have not become more virtuous, more civilized, or more humane. The same questions about what makes us human that we have always had to confront are still with us. They are arguably more pressing now because of the dislocations and alienations caused by technology. But to judge by contemporary nihilism and unhappiness, the 21st century has not yielded any good answers so far, and no amount of innovation will help.

‘Is there any thing whereof it may be said, See, this is new? it hath been already of old time, which was before us’ (Eccl. 1.10). Those are the famous words of Ecclesiastes, the Preacher in the Hebrew Bible who ‘communed with [his] own heart’, and realised that ‘there is no new thing under the sun’ (Eccl. 1.16; 9).

Somewhat more comforting words on the same theme were written by Marcus Aurelius in the same spirit of private reflection. The rational soul, Marcus said,

goes over the whole universe and the surrounding void and surveys its shape, reaches out into the boundless extent of time, embraces and ponders the periodic rebirth of the whole and understands that those who come after us will behold nothing new nor did those who came before us behold anything greater, but in a way the man of forty years, if he have any understanding at all, has seen all that has been and that will be… (Meditations, 11.1)

Perhaps we are finally ready to hear this again.

Fun fact: I actually bought my copy of Dover's Greek Homosexuality at a street market in Dar es Salaam in 2006. There must have been a vogue for the classics in Swahili-speaking lands at that time...

Having just read Henrich's book 'The Weirdest People in the World,' I wonder if the way the West broke up kinship networks and traditional clans has something to do with this. We're less likely to define ourselves through genealogy - and perhaps that applies to cultural as well as genetic relationships, to our identity as a culture as well as individuals.

It may be, in any case, that most other cultures just don't construct strange mythical narratives about how they don't descend from the ancients.

A great read. I'll be checking out your book. Do you see the Arabic translation movement under the Islamic Empire as being a continuation of the pre-Islamic education/scholarship efforts of the Sasanian kings?

I like your emphasis on the cross-pollination of ideas sparking intellectual resurgences in areas where the embers of learning had previously died out. Modern framing often makes it seem like these things happened in a vacuum.